Yoga Breathing for Health

Yoga Breathing for Health: Breathe Slowly, Exhale Fully — Sixteen Ways to Slow Breathing and Lengthen Exhalation

Almost everyone including people with asthma or COPD (Chronic Pulmonary Obstructive Breathing) can benefit from breathing slowly and exhaling more completely. Benefits of slow breathing and longer exhalation are many. To wit: Greater control over breathing; reduction in shortness of breath and breathing discomfort; increase in physical and mental relaxation; relaxed breathing and more open airways which can transport air in and out more effectively.

By breathing slowly and lengthening exhalation relative to inhalation, lungs can be more effectively emptied out and filled, old and stale excess air eliminated and hyperventilation (over breathing) and hyperinflation of lungs (enlargement of lungs due to surplus air) 1 can be modified. Actually, benefits of the breathing pattern of slow breathing and longer exhalation are too numerous to list here.

You are likely to hear from yoga teachers who teach a breath-centered practice such statements as, “Exhalation is the key,” “Take care of the exhalation and inhalation will take care of itself,” or simply the instruction, “Exhaaale!” encouraging you to prolong your exhalation. These instructions may seem very counter intuitive because most people instinctively believe inhalation is most important. Yogis from ancient times practiced conscious and controlled breathing, called “pranayama.” They extensively worked on strengthening abdominal muscles in order to exhale more fully. Their morning breathing practices to a large extent consisted of gentle, slow and long exhalation and inhalation and only to a small extent that of vigorous exhalation and inhalation. In this article, we will discuss a number of gentle and slow breathing techniques.

Try them and see which one’s work best for you.

Pranayama and breath coordinated yoga postures (asanas) can help us to slow our breathing and lengthen our exhalation. I have personally practiced some time or the other all the techniques discussed in this article. They have helped me to reduce shortness of breath and increase my stamina and exercise tolerance.

Developmental Work for the Breathing Exercises

- Maintain breath awareness for most part of the day. Stay conscious of your breathing whether you experience any breathing difficulty or not. Try to maintain breath awareness while walking or performing other exercises and activities. Develop a keen sense of breath awareness at all times, whether resting or exerting

- Walk every day

- Perform gentle stretches and upper body exercises including trunk flexion several times a week.

- Become an expert of Pursed-Lip Breathing (PLB): PLB is well known to build positive air pressure in the airways in order to exhale more effectively and completely. Instructions for PLB are widely available in the respiratory literature. To instruct briefly, inhale through your nose, purse your lips like you would while whistling or kissing and exhale maintaining consistent flow and pressure of breath. The technique of pursed lips can be applied to many of the exhalation techniques described in this article. The ancient technique of chanting “Om” in India is a type of PLB technique.

Cautions/Guidelines

- Practice breathing exercises while maintaining physical and mental relaxation.

- Don’t strain your breath! Rest in between as long, and as many times as needed. Don’t force your breath. Follow the mantra, “Coax it. Don’t force it.!” Stay within your comfort zone at all times.

- Start with one or two techniques. Gradually increase the length of the breath and the number of repetitions of each technique.

- Some techniques may feel more comfortable and natural to you than the others. Adopt the ones you like for your daily practice.

- Know your limits. Some days you may not be able to do as much as you did the other day. Still another day, you may find a technique difficult which was easy the day before. Know what you can do that day and how far you can challenge yourself that day by recognizing when you are approaching your exertion limit, and slowing down or stopping before you develop severe shortness of breath.

The sixteen (16) ways to cultivate slow breathing and lengthening exhalation are divided into following categories:

- Predominantly Physical techniques

- Predominantly Mental Techniques

- Breath Manipulation Techniques

- Breath Vocalization

- Alternate Nostril breathing Techniques

- Instrumental

Don’t take the categories literally or mutually exclusive. They are loose “baskets” to hold somewhat similar techniques in order to make it easier to put our arms around them.

Predominantly Physical Techniques:

- Breath coordinated spinal movements (asana)

- Relaxation pose (Shavasana): Relax and exhale! Exhale and Relax!

Predominantly Mental Techniques

- Forming intention for longer exhalation (Sankalpa)

- Tracking the Breath flow (Sakshi)

Direct Breath Manipulation

- Silently count the length of each breath (shavasa-prashavas sankhya)

- Count only the exhalations (Prashvas ganana)

- Inhale partially, exhale fully (visham vritti 1)

- Inhale passively, exhale actively (visham vritti 2)

- Segmental Exhalation (Viloma krama)

- Body locus breath (Yoga nidra breathing)

Breath Vocalization

- Humming breath (Bhramri)

- Vowel singing (Omkara)

- Whisper chanting

Alternate Nostril Breathing Techniques

- Partially closed nostril alternate nostril breathing (anuloma viloma variation)

- Exhaling through the dominant nostril (nadi shodhna variation)

Instrumental

- Exhalation props (prashvasa sopashraya)

Predominantly Physical Techniques:

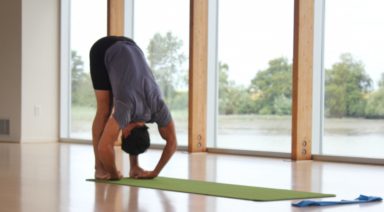

- Breath coordinated spinal movement (Asana): Utilize postures which facilitate exhalation such as forward bending, lateral flexion and spinal twist because they make it easier to exhale more fully. Examples:

- In the standing, sitting or kneeling position, while exhaling slowly bend forward

- In the sitting position, press the floor or hold the chair seat with one hand while exhaling raise the other arm and bend laterally

- In seated or reclining position, while exhaling perform an abdominal twist. Select low intensity stretches to avoid excessive work for the muscles. Perform several repetitions of the same posture slowly and smoothly. Progressively lengthen your exhalation during these repetitions.

By coordinating and manipulating the speed of breathing and movement into and out of a posture you can progressively lengthen your exhalation. Example: Sit on a chair with arms by your side. Press hands on both sides of the seat. While elongating your spine, inhale to of your lungs. While exhaling, start bending forward. Adjust the speed of forward bending movement so it lasts as long as your exhalation does. The extension of exhalation, in parts, depends on how slowly you bend forward, how slowly you exhale while bending forward and how far forward you bending.

- Relaxation Pose (Shavasana): Relax and exhale! Exhale and relax! Relaxation is the master skill for breathing retraining. Shavasna, the reclining relaxation pose is excellent for relaxing and deepening the breathing and extending exhalation. When you are relaxed, breathing automatically gets slow and soft, diaphragmatic breathing restored and all stress related breathing irregularities are reduced. Several times a day, take a few minutes each time to relax physically and mentally. With calm and quiet mind, relax the whole body. Imagine you are in a peaceful, quiet and relaxing place. Relax the entire face including the jaw, neck and shoulders and then the rest of the body. Continue to relax and exhale. With each exhalation, relax even more than before.

Predominantly Mental Techniques:

- Forming intention (Sankalpa) for longer exhalation: Intention is well known to inspire action and affect the outcome. Therefore, form the intention of slowing your breathing and lengthening your exhalation. Be patient and relaxed about your intention. You can’t change your breathing in a hurry. Keeping your new intention at the back of your mind let the exhalation extend. When you remain calm and relaxed and mindful of your intention, breathing is likely to become soft and slow, and exhalation might begin to “stretch” longer than inhalation. Try not to inhale deeply or fully. Allow the exhalation to extend longer without straining your breath.

- Tracking the breath flow (Sakshi): Bring your mind to breathing. Don’t judge it, simply witness it. Track the flow of the breath during inhalation and exhalation without tension, rush or anxiety. While inhaling, move your attention downward from chest to abdomen. While exhaling, move your attention upward from pelvis to solar plexus. In other words, track the downward flow of breath as you inhale and upward flow of breath as you exhale.

According to the Viniyoga tradition and in my own experience as a person with COPD, tracking inhalation downward and exhalation upward is enjoyable and comfortable. However, some people are more comfortable with tracking inhalation upward and exhalation downward. Whichever works better for you is the one you should practice. There is a cute saying in yoga circles, “Breath flows where attention goes.” So it all works out. All you need to do is to track the breath flow. Paying attention to the direction of the breath flowing upward and downward in the ribcage and abdomen is likely to relax you, slow the breathing and lengthen the exhalation.

Direct Breath Manipulation Techniques

- Silently count the length of each breath (Shvasa-prashvasa sankhya): Simply counting silently in head while breathing automatically slows and relaxes the breathing for most people. Example: While inhaling, silently count in your head by saying “one thousand one” “one thousand two” “one thousand three” “one thousand four.” While exhaling also silently count, “one thousand one” “one thousand two” “one thousand three” “one thousand four.” As you continue, increase your count for exhalation, for example, up to 1005 or 1006 while still keeping the inhalation up to 1004. Maintain the ratio of inhalation and exhalation as 1 to 1.5 or 1 to 2. Does keeping a count while breathing make you tense? Do you try very hard to maintain the same ratio or try to lengthen the breath too early and too hard?

It is important to be patient and relaxed about breathing. If counting makes you tense in trying to keep the same number then let go of the count. Use your judgment to maintain the exhalation longer than inhalation (refer to “Inhale partially, exhale fully.”). All you have to do is to inhale less fully and exhale more fully. If you feel all right about breath counting, adopt the practice in your daily life. Wherever and whenever you remember to do it, start counting (1001, 1002, 1003 and so on) as you inhale and exhale. You may do this while sitting, standing, walking, working, performing an activity or exercising.

- Count only the exhalations (Prashvasa ganana): Inhale briefly. Exhale and towards the end of exhalation say silently or out loud, “One!” Again, inhale briefly. Exhale and as you near the end of that exhalation say, “Two!” Repeat and with each subsequent exhalation, count the next number “three,” “four” and so on until you complete ten exhalations in this manner. To increase the sense of relaxation and lengthen exhalation, each time as you exhale, let your body become loose and limp and say the number in a soothing and soft tone such as, “Onnne!” “Twooo!” “Threee!” and count up to 10 exhalations. If time permits, repeat another round of ten exhalations.

- Inhale partially, exhale fully (Viloma visham vritti 1): When you inhale, simply stop inhaling or 2/3rd or 3/4th of way, but exhale more fully without forcing or straining your breath. Progress gradually in favor of longer exhalation. Maintain the ratio of 1: 1.5 or 1: 2 between inhalation and exhalation. In other words, keep the exhalation one and one-half time or twice longer than the inhalation. Example: 4 second inhale and 6-8 seconds exhale or 5 seconds inhale and 7-10 seconds exhale.

- Inhale passively, exhale actively (Viloma visham vritti 2): Inhale passively by simply allowing the inhalation process to occur, but while exhaling, mildly engage the abdominal muscles by gently pulling the lower belly towards the back. It is gentle “forced expiration.” Use only gentle force and mild contraction of abdominal muscles while pulling in the navel towards the back.

- Segmental Exhalation (Viloma krama): Inhale in one continuous stretch but split your exhalation in two segments. Here are the instructions: Inhale in one continuous breath. Then, slightly contract your lower belly, that is, pull it in towards the back from pelvis to the navel and exhale the way. Pause for a second or two and then contract your belly from navel up to the solar plexus while finishing the other half of your exhalation. When you get really good at 2-segment exhalation, you may 3-segment exhalation. For example: Inhale! Pause for a 1-2 seconds and then exhale 1/3rd while contracting perineum to pelvis. Pause for 1-2 second and exhale another 1/3rd while contracting from pelvis to the navel. Pause for 1-2 seconds and complete the last 1/3rd of the exhalation while contracting the abdomen from navel to the solar plexus.

- Body locus breath (Yoga nidra breathing): True, we all breathe in and out through nose and occasionally the mouth. But in this exercise we IMAGINE breathing in and out through other body locations. Here is the exercise in imagination in order to increase the exhalation: Each time as you inhale, imagine the in-breath entering through the crown of your head and ending in the heart region. Each time as you exhale, imagine the out breath starting from the heart region going all the way down and exiting through the toes and soles of the feet. In short, imagine inhaling through the crown of the head to the heart and exhaling from the heart to the toes and soles of the feet. This exercise can be done while sitting or lying down, though most relaxing when you are lying down.

Breath Vocalization

- Humming breath (Bhramri): Inhale briefly, softly and slowly with your nose. Exhale with soft humming sound prolonging your exhalation but without straining your breath.

- Vowel singing (Omkar): Inhale briefly, softly and slowly with your nose. While exhaling sing a vowel such as “aahmm” “eeem” or “ooomm” prolonging your exhalation but without straining your breath. If you don’t fancy singing vowels, you may sing consonants to prolong your exhalation. Example of consonant singing: Inhale briefly, softly and slowly with your nose. While exhaling sing “Sa, ta, na, ma,” “Sa, ta, na, ma,” “Sa, ta, na, ma,” “Sa, ta, na, ma,” as long as your exhalation lasts without straining your breath.

- Whisper chanting: Begin singing these four consonants in a soft whisper: “Sa, ta, na, ma,” “Sa, ta, na, ma,” “Sa, ta, na, ma,” “Sa, ta, na, ma,” and so on as long as your exhalation lasts without straining your breath. As you begin inhaling, continue singing these four consonants in soft whisper for a brief inhalation (filling in one half or two thirds of your lungs). Thus, form a continuous cycle of singing the consonants in whispering breath, inhaling and exhaling without straining your breath. The moment you feel any sign of fatigue or strained breath, stop and take rest. Whispering is unique because you can continue singing during exhalation as well as inhalation. Your exhalation should remain longer than inhalation. For example, repeat sa, ta, na, ma 4-5 times during inhalation and 6-8 times during exhalation.

Alternate Nostril Breathing Techniques

- Partially closed nostril alternate nostril breathing (Anuloma-viloma variation): Alternate nostril breathing should be done on a day when the nostrils are not blocked. In the traditional alternate nostril breathing, we keep one nostril fully open for breathing and the other fully closed. But in this variation of alternate nostril breathing, instead of keeping the nostril completely open, we partially close. By partially closing the nostril we create a “valve” for breathing in and out. Technique for “valved” nostril breathing: Close one nostril completely by applying the pressure of thumb or fingers on the flap of the nostril (the lower portion of the nose). Partially close the other nostril by gently pressing the cartilage in the upper nose with your fingers or thumb.

Thus, the valved nostril remains partly open for exhalation or inhalation and thus helps you to control the flow and the volume of the breath. By crafting a valve in the nostril, you can further increase the differential between inhalation and exhalation. You can close inhaling nostril with little more pressure and a little less pressure at the exhaling nostril. In this way, you can further affect the flow and amount of air you exhale and inhale. At any rate, make sure you manipulate the valve in such a way that exhalation works out to be longer than inhalation.

- Exhaling through the dominant nostril (Nadi shodhana): Several times a day, there is a shift in breath flow from one nostril to the other. As a result of this shift one nostril registers greater flow of breath compared to the other. This phenomenon is refered to as, “ultradian rhythm of the nasal cycle.”2 Incidentally, the shift in nasal cycle is also associated with the shift in the dominance of the right or left brain hemisphere. To identify which nostril is dominant at a given time, close one nostril and exhale against the back of the hand. Now repeat the process with the other nostril. Which nostril appears to exhale more fully? Utilize the dominant nostril for exhalation and passive nostril for inhalation for just a few breaths.

Instrumental

- Exhalation Props (Prashvasa sopashraya): There are a number of aids we can use to extend exhalation. To wit: woodwind instruments such as flute; harmonica; whistle; whistling, etc.

End Notes

- For a comprehensive discussion of the physiology of overinflated lungs and hyperinflation, refer to Deane Hillsman, M.D website on COPD self-help at http://www.sierrabiotech.com/bt_copd_home.html

- David Shannahoff-Khalsa reviews studies of lateralized ultradian rhythms of EEG during wakefulness showing a correlation between hemispheric dominance and the nasal cycle. Refer to Khalsa’s paper The Ultradian Rhythm of Alternating Cerebral Hemispheric Activity, (International J. of Neuroscience, Vol 70, issue 3 & 4 June 1993, pp 285-298.

Changes in the relative fight-left brain hemispheric activity occurs several times a day and the hemispheric changes appear to be associated with the right left nostril air flow, referred to as “nasal cycle.” At any given time, one nostril is more open and has the greater amount of air flow which may partly be due to congestion and decongestion of the veins lining the nasal mucosa. This alternation of right and left hemisphere dominance and changes in the air flow in the right and left nostrils occur at varying intervals in the individuals ranging from about half an hour to 5 hours with peaks between 90-200 minutes during waking. This phenomenon also occurs during night at varying time intervals for individuals (some of the results of Google search for “Ultradian rhythm of nasal cycle”).

What is Pranayama?

Yoga as a practice has ancient origins. The first textual mentions of the term can be found in the Rig Veda, which was written around 1500 BCE. While nobody knows exactly how old the practice is, some scholars believe that members of pre-Vedic societies practiced yoga even before that time.

The early yoga of the Vedas was much different that what we practice today. While many modern yoga practitioners have come to associate yoga with the performance of physical postures (asana), all of the earliest recorded texts on yoga hardly mentioned postures at all, and instead tended to emphasize the pursuit of liberation through meditation and pranayama practices instead.

What is Pranayama?

The word pranayama is a compound of two separate Sanskrit terms, prana and yama. The Atharvaveda, (one of the earliest Vedic texts on Indian medicine) states that prana is “the fundamental basis of whatever is, was, and will be.” Other texts often translate prana, as the “life force” or “vital energy”. The complementary term yama is often translated as “restraint” or “control”.

Pranayama then, is typically defined as a set of practices designed to control prana within the human body by means of various breathing techniques, meditative visualizations and physical locks (or kumbhaka).

The Sanskrit language is incredibly rich, and like many languages, one word can often have many different meanings. Some scholars, such as Harvard University Buddhist Chaplain Khenpo Migmar Tseten, prefer to separate the components of the compound into pran and ayama for the purposes of translation. When broken up in this way, pranayama becomes pran, (life-force), and ayama (which has the meaning of expansion or extension). In this case, the conjoined term pranayama takes on the meaning of “expansion of the life force”.

The Benefits of Pranayama

In his book Samadhi of Completion: Secret Tibetan Yoga Illuminations for the Quing Court, Fransoise Wang- Toutain states that “Prana is the driving force of all the functions of the body”, and that “the various functions of the body such as swallowing, digestion, and physical movement were all reliant of the efficient functioning of the prana within the body.”

According to Wang-Toutain (and the tenants of Indian medicine), the roots of all disease and mental imbalance can be traced to abnormalities and deficiencies in the body’s energy flow. In Wang-Toutain’s view, pranayama practices serve as a particularly powerful tool to heal illness and correct mental imbalances since “the control of breathing is the most direct method to affect life force.”

The History of Pranayama – A Timeline

The following timeline gives a general bird’s eye overview of the history of pranayama practices. Though this list is neither intended to be exhaustive nor comprehensive in its scope, it includes a small number of key texts that will be of interest to anyone who wishes to learn more about the history and practice of pranayama.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

(Circa 700 BCE)

While references to the the term prana can be found as early as 3,000 BCE in the Chandogya Upanishad, references to pranayama as a breathing practice do not occur until much later in yogic literature (approximately 700 BCE).

One of the earliest recorded references to pranayama as a breath related practice can be found in hymn 1.5.23 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. Clearly linking breathing practices to the regulation of vital energy and life-force, the Upanishad states:

“One should indeed breathe in (arise), but one should also breathe out (without setting) while saying, “Let not the misery that is dying reach me.” * When one would practice that (breathing), one should rather desire to thoroughly realize that (immortality). It is rather through that (realization) that he wins a union with this divinity (breath), that is a sharing of worlds.”

No additional guidelines for pranayama practice are given in this Upanishad. However, the idea that breathing could be used to achieve greater health and even immortality is a theme that is often repeated in subsequent yogic texts and teachings.

The Bhagavad Gita

(Circa Fifth Century to Second Century BCE)

References to pranayama practices can also be found in the Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 4, verse 29. The text highlights the use of conscious inhaling, exhaling and breath retention to effect trancelike states. The text also suggests that the regular practice of pranayama can be used to enact greater control over the senses by “curtailing the eating process.”

The Maitrayaniya Upanishad

(Circa 4th Century BCE)

The Maitrayaniya Upanishad is an important text in the history of pranayama because it contains one of the earliest references to pranayama as a component in a larger, multifaceted system. Most likely composed centuries before the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, this text enumerates yoga as a six-step process of breath control (pranayama), sensory withdrawal (pratyahara), concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), reasoning (tarka) and union (samadhi).

Specific references to pranayama practices can be found in chapter six, verse 21. The text states that deliverance can be accomplished by using a combination of breath retention practices and concentration on the sacred syllable Om in order to redirect prana into the body’s central energy channel (Sushumna).

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

(Circa 100 to 400 CE)

Most scholars agree that the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are a compilation of texts from earlier yoga traditions. By the time of Patanjali, yoga as a system had continued to adapt and grow. The six-limbed system mentioned in the Maitrayaniya Upanishad had grown into eight limbed approach that included asana (physical postures) yama and niyama (social and ethical precepts) pranayama as well as four additional stages of meditative absorption (pratyahara, dharana, dhyana and samadhi).

References to pranayama can be found in verses 2.29 – thru 2.53 of the Sutras. While Patanjali does not go deeply into the nature of prana in these sections, he does detail four separate aspects of the breath: inhale, exhale and retention. In addition, Patanajali also makes reference to a fourth pranayama in sutra 2.51 that he claims surpasses or goes beyond the other three.

In addition, Patanjali notes a number of specific benefits of pranayama practice. These benefits include mental fitness and the ability to concentrate – a prerequisite to deeper states of yoga practice. Additionally, Patanjali states in verse 2:52 that regular pranayama practice could lessen or dissolve the veil that covers our “inner illumination.”

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika

(Circa 1500 CE)

Though traditionalists trace the roots of Hatha Yoga practice to the God Shiva, many scholars associate the founding of the Hatha yoga movement with the Maha Siddha Goraksha Nath. Widely associated with being the founding father of the practice, Gorakshanath is purported to have lived sometime between the 10th and 15th century CE. Numerous texts are accredited to him and his disciples.

One of the most important texts of the medieval era is the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, which was written by Goraksha Nath’s pupil Swami Svatmarama. Drawing from earlier systems, the text emphasizes the attainment of good heath and spiritual realization through a combination of physical postures, pranayama practices and meditative contemplations.

The Pradipika differs from some of the early texts in the history of pranayama, because it more fully details actual instructions for practice. These instructions include specific references to alternate nostril-breathing patterns, details on how to retain the breath, guidelines on auspicious times for practice and an overview of the various signs of progress in pranayama.

Further references to pranayama techniques can be found in a number of additional medieval manuscripts. The most important of these texts include the Gheranda Samhita (late seventeenth century) and Shiva Samhita (seventeenth or eighteenth century CE).

Pranayama Today

While most modern pranayama practices are based at least in part on their original counterparts, contemporary pranayama practices often include a number of additional variations on the basic breathing patterns found in the earlier texts mentioned in this paper.

Modern variants on the practice tend to integrate a combination of modern anatomical knowledge with more traditional yogic teachings in order to refine technique and better explain the physiological and psychological processes that occur when practicing pranayama.

The most notable example of this new approach to pranayama practices can be found in the book “Light on Pranayama”, by the the late B.K.S. Iyengar. A seminal text on modern day pranayama practice, Iyengar’s book is a must read for any student with an interest in the history of pranayama.

Where Should I Begin?

Pranayama practices are best learned under the guidance of a qualified instructor. Though not commonly known, many Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns practice traditional Hatha Yoga pranayama exercises that can be traced to the 9th century CE. Many contemporary yoga teachers offer pranayama as part of their classes as well. This video on Gaia is a great place to start if you wish to begin the practice.

A Short Exercise for Home Practice

If you wish to begin practicing today, consider trying this alternate nostril breath from the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.

To begin:

- Come to a comfortable crossed legged position

- Block your right nostril, and inhale slowly through the left.

- Hold your breath for a few counts, and then exhale slowly through the right nostril.

- Block your left nostril, and inhale slowly through the right.

- Hold your breath for a few counts, and then exhale through the left.

Repeat the entire cycle for a minimum of seven repetitions. As you become accustomed to the exercise, practice for longer durations.

Practice notes: If holding your breath is uncomfortable at first, begin with very short breath retentions. As the practice becomes more familiar, gradually extend the length of the retention. Breath retention is contraindicated for expectant mothers.