Have Niche Yoga Styles Taken It Too Far?

What does yoga look like when no one is looking?

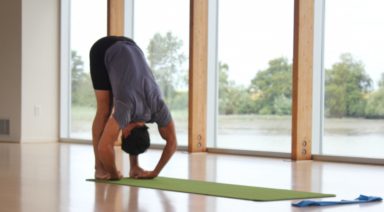

The answer to the question depends on who we are watching. What yoga looks like can vary widely, especially because there are 4 main kinds of yoga: The yoga of intelligence (jnana), the yoga of devotion (bhakti), the yoga of service (karma), and hatha yoga which is the one we think of when we see people doing downward dog. Yoga for one person may look like studying scripture and attending dharma talks. While for someone else, it’s doing service to their community without expectation of getting anything in return.

For another individual, yoga is chanting and repeating the same kriya for an hour every single day. Someone doing an hour-long physical yoga class, breathing, resting at the end, and saying “OM” might be more of what we’ve come to recognize yoga as today. So whether sitting silently on a cushion for hours or doing plank while drinking a microbrew, we can technically call it yoga.

If you ask someone in the East, someone in the West, someone today, and someone from the past, their answers can vary as widely as the styles of yoga offered. So is any of the yoga we see taking it too far?

Is ‘fun and done’ yoga still yoga?

People have short attention spans. Multi-tasking is the norm. We are accustomed to 15-second commercials, next day delivery, 18-minute educational Ted Talks, and seven-minute workouts. We want things quickly and we want results now. Oh, dopamine! We want to click on one tab to bring us to another and then we get lost down a rabbit hole on the internet, rather than complete one task, we get lost in the shuffle. This spastic and brain-draining way of using our attention lacks depth, true focus, and the willingness to delay gratification. Delaying gratification comes with a number of benefits. That is why a lifelong practice of yoga can be ultimately gratifying with dedication over a lifespan. So is there value in the ‘fun and done’ niche yoga world?

The short attention span culture we live in craves a constant stream of entertainment and novelty. We want things catered to our exact interests and we want it now. More than 36 million Americans are practicing yoga (source: Harvard Health Publishing). Because we are used to being consumers in this strange new world, we can expect there to be yoga to meet our exact demands. Therefore, it makes sense that we provide many kinds of yoga that feel fun, trendy, and Insta-worthy. But if we cannot take these experiences for fun and then integrate them into a regular yoga practice, then perhaps we are taking it too far. On the other hand, if we can draw new people into yoga, bring joy and provide much needed in-person socialization, culture, and entertainment, we are providing a tremendous value that people are willing to show up for it.

I have to admit I have scoffed at goat yoga and rolled my eyes at beer yoga. These new trends in yoga popped up after others that have been around and once seemed unconventional.

SUP yoga is yoga on paddleboards, yoga-pilates fusion combines two forms of exercise and is less meditative and more exercise-focused, and chair yoga allows people to do poses while supported by chairs. These different offerings became the norm to give athletes, the elderly, and everyone in between an entry point into yoga. They have become fixtures in our modern yoga world. And now, niche classes such as yoga at art museums and breweries get people’s attention and match their interests. These special event yoga classes are the SUP and vinyasa yoga of today, drawing huge crowds, big money, and hopefully helping people.

Individuals that may otherwise skip yoga are drawn to these classes. Some of the attendees may be newcomers to yoga. These trending classes may also attract regular yogis that typically go to the same classes with the same instructors, reinvigorating their enthusiasm for yoga and connecting them to others. Perhaps the novelty keeps it feeling fresh and new while giving practitioners a way to socialize face-to-face.

The end result of all these offerings is people experiencing yoga. And if it brings them into themselves, facilitating a march down a healing path, even if it isn’t traditional, then there is a benefit. The caveat being that the new yogi also goes beyond the fun to truly experience yoga as it is designed. If people are only coming to yoga for the fun, then it is being stripped down to an unrecognizable form. After all, the poses being taught at these events are only one of 8 limbs of the yoga path, and hatha yoga is only one of the 4 pillars of yoga. There is more to experience and more to study.

How to Stay True to Yoga at a Specialty Class:

-

Connect to your needs and meet them on the mat.

-

Remember to breathe.

-

Pause to experience gratitude.

-

Feel your body.

-

Notice your surroundings.

-

Relish in a quiet moment of prayerful meditation.

-

Thank your teacher.

Everyone Has a Specialty

As more and more people become certified to teach yoga, the business model of teaching studio classes can not pay the bills for everyone. For economic reasons newcomers and veterans teachers alike have been forced to think outside the box. They want to cater to people’s lifestyles and interests. Therefore yoga at museums, on hotel poolsides, and on surfboards makes financial sense.

There is a desire to tailor yoga to instructor expertise. As a result of more people attending yoga trainings, different specialities are popping up based on the professional and academic backgrounds of graduates that seem to create something entirely new. Therefore, with a combination of a wide variety of practitioner interest and ability, an economic need for novel class offerings, and the diverse expertise of instructors, we can continue to expect new yoga fusion cocktails to be mixed up. And should we drink them up?

It is a personal decision for each yogi to make regarding the style, frequency, and commitment we make to yoga. Power to the people that enjoy teaching or attending large public classes on a farm or in a microbrewery. Still, the shift we seek from yoga will only happen from regular, dedicated practice of integrity. Yoga can look like a lot of things. We can choose from such a wide variety of yoga. So then the question must shift from, ‘has yoga gone too far? to ‘how do we want to feel as a result of our practice?’It is then we can make an informed decision. It is then we can be empowered by choice.

Yin Yoga Benefits and History

Maybe you’ve heard of yin yoga but don’t really know what it is. Maybe you’ve tried it but lack some understanding of its origin or purpose. Or perhaps this is the first you’re hearing of it.

This exploration of the benefits and history of yin yoga will provide you some understanding of where yin came from and how it benefits people. If you find it compelling, get on your mat, keep learning more, and let us know how your journey unfolds.

To prepare for this article, I interviewed several Boston-based yin yoga teachers and regular practitioners. This is their scoop, filtered through some of my own experiences on what the benefits of this slow, meditative practice are.

What are the Benefits of Yin Yoga?

Seeing Within

When practicing this turtle-paced yoga style, unlike other varieties that are fast-moving and fancy looking, there is no wow-factor for spectators. Because yin yoga stretches connective tissue, especially at the joints, difficult inversions and impressive poses wouldn’t be safe considering how long they are to be held (anywhere from a couple of minutes up to around 20 minutes). To experience the wonders of yin, practitioners simply hold well-aligned, basic poses.

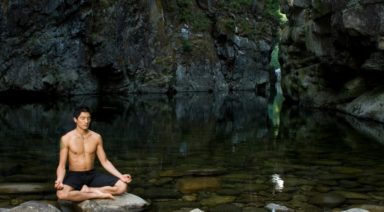

Doing poses in stillness promotes the cultivation of the inner life.

As yin yoga enthusiast Kourtney Hartmoyer has so eloquently put it, “the shapes are simple, perhaps even boring. To the outside world, it doesn’t look too interesting. However dull from an outside view, what I have found is that the quiet stillness of yin allows me to better observe the inner self a bit more clearly. It magnifies everything. That is where I find the magic.”

I have felt the magic, too. Yin yoga helps me to see myself on a deeper level through the cultivation of stillness. When I practice it’s not always easy or even possible to become physically still. Yet when I am able to “drop-in” and become motionless, the depth of awareness is simultaneously awe-inspiring and intrinsically peaceful. I can watch the inner play of my mind and subtle body as an observer. I can see within.

If you are planning to start a yin practice, it’s okay not to be absolutely still. It’s okay to struggle. The struggle contains information you can observe with kindness and curiosity. And when it finally subsides and you can be still, you can move deeper into yourself and into greater states of euphoric relaxation.

Moving Into Deeper States of Relaxation

Joanna Barrett told me that her daily yin practice helps her “to sit with sensation, moving toward or into deeper states of relaxation.” Moving quickly cannot promote deep trance-like states in the manner utter stillness can. If you’re curious, swap out the vinyasa flow for a yin vibe to appreciate what Joanna is talking about.

The depths of relaxation may require some preparation and commitment of time. It wouldn’t make sense for you to rush into a meditative state.

You’ll need time to allow your body to slowly drop into the depths of each pose. Completely support yourself with props, breathing deeply with lungs that move air like the bellows that feed fire.

Sure enough, the depth of sensation will tempt you to get out of the pose. I urge you to remain still while breathing deeper to experience the peace and meditation of true surrender. Can you stay just a little longer and relax just a little more? That might require a great deal of patience.