Addressing Our Scapular Stabilizers

Developing Our Scapular Stabilizers to Prevent Shoulder Injury.

What constitutes a shoulder joint that is prone to injury? Could it be weak rotator cuff musculature? Maybe it is joint laxity and instability? What about capsular restrictions or the work we do on a regular basis? Or, is it possible that weak scapular stabilizers could play a role in shoulder injury?

The answer is, all of the above reasons could contribute as the cause of a shoulder injury. Although shoulder injuries are often complex, many do happen to be related to one common problem: weak muscles that support the shoulder blades, otherwise known as scapular stabilizers.

The scapula (shoulder blade) is a very involved structure of the body. Not only does this bone articulate with the humerus (upper arm bone) and clavicle (collar bone), it is also the attachment site for many muscles in the shoulder itself, as well as the back, the chest, the arm, and even the neck. It is therefore easy to comprehend how a weakness in this area could affect many others in the body.

The muscles that attach on the medial (inside) aspect of the scapula are the key muscles for scapular stabilization. These include the middle trapezius and lower trapezius, rhomboid major, and rhomboid minor, and serratus anterior. The middle trapezius and rhomboid muscles function to retract the scapula. Scapular retraction is the action of squeezing your shoulder blades together. The lower trapezius takes care of scapular depression which is drawing the scapula down the thorax. The task of serratus anterior is to hold the scapula’s medial border tight to the thorax.

Many of these weaknesses are actually observable. When the lower trapezius muscle is weak, a flaring of the lower scapula exists. When the serratus anterior is weak, the medial border of the scapula flares. Weakness of the middle trapezius and rhomboid muscles contributes to a separation of the scapulae, also known as protraction.

It is therefore the job of these muscles to hold the scapulae tight to the thorax. If the scapulae are not held firmly by strong muscles, they are left free to flare and flop with arm movements. Without stability at the scapula, how is it possible for the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) to remain stable? It isn’t.

Scapular instability leaves the glenohumeral joint (GH joint) at risk of injury as the GH joint requires both strength and endurance of scapular stabilizers for it to be protected. The stability of the GH joint cannot come from the humerus since the arm does not have anything to stabilize from; it has no anchors. However, the scapula attaches to the axial skeleton of the body (a fantastic anchor) and therefore can generate stability from the thorax. Strong scapular stabilizers have been proven to defend the GH joint from injury.

Once these weaknesses are identified via observation of functional movements and muscle testing, exercises must be incorporated into one’s daily schedule in order to prevent or rehabilitate shoulder injuries. Many of the exercises used to target such muscles are very intricate in their movement patterns and look fairly easy. Often, the first time patients see these exercises performed, they expect them to feel simple. However, as soon as they attempt one repetition themselves, they recognize how weak their stabilizers actually are and appreciate the need for such training.

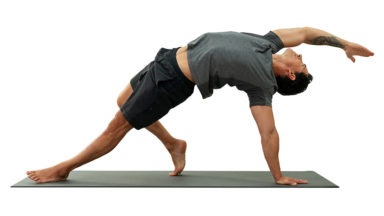

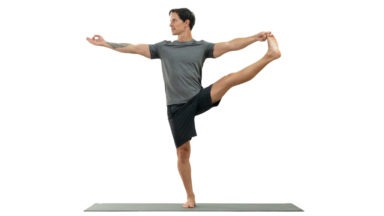

Typical yoga posture focuses heavily on scapular retraction and depression. Yoga brings these movements into everyday life. If you meet a yogi, their scapulae will be retracted and depressed. Their shoulders will not be around their ears like the rest of the population who carry their tension in their upper trapezius muscles and levator scapulae. Simply applying these two movements to your daily activities will prove beneficial. However, to truly protect the GH joint from injury, more intensive exercise is required.

Yoga, single-handedly, can not target each of the scapular stabilizers appropriately, unless modifications are made to poses or practices. For example, by the addition of scapular protraction to plank pose, the serratus anterior muscle could be optimally targeted. Many of the movements designed to pursue the scapular stabilizers are very specific. Feedback from a health care professional or yoga instructor is ideal when attempting to understand these movements.

Bring attention to these muscles in your back. The benefits you will gain from strengthening these muscles are plentiful. Whether you are a parent who is constantly picking up children, a housewife who places the dishes in the top cupboard, or an athlete who is involved in sports with overhead movements such as tennis, volleyball, or climbing, scapular stabilization is essential in preventing shoulder injuries.

Explore the Anatomy and Correct Alignment of Headstand Pose

Knowledge dissolves fear. With a basic understanding of the structures in your neck, and application of these five keys, one can practice sirsasana safely.

Let’s first take a look at the anatomy, and the neck’s role in our daily life.

The seven little bones of the cervical spine (neck bones) are unique in that they are designed for mobility rather than stability. Like other joints in the body, where stability is sacrificed for mobility, the primary purpose of the C spine in daily life is ease of movement. Therefore, ideal alignment and muscular harmony are particularly important.

The load bearing structures of a cervical vertebrae are the body and two articular facets. A typical cervical vertebral body is approximately two centimeters in diameter depending on the vertebrae (C3 – C7), gender, and individual differences. This is comparable to the diameter of a dime. One may make the comparison of a lumbar vertebral body and cervical vertebral body to the chunky heel of a walking shoe to a high heeled pump. Imagine walking a gravel road in stilettos versus the former.

Another feature worth noting is that the C spine houses the vertebral arteries. Transverse foramen, or holes from top to bottom on the side wings of the bones, house this paired blood vessel which travels up to the brain, taking a rather alarming posterior jog at the top of the neck bones before entering the skull. Symptoms of blocking this small artery include dizziness, blurred vision and occipital headaches. Any lesion compromising the integrity of this passage way is exacerbated by misalignment and the additional and uncustomary weight of your body on the cervical vertebrae in a posture like sirsasana.

Nerves exit the intervertebral foramen (holes in the sides between the neck bones), the branches of which pass laterally between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. These muscles help to hold your head and neck up like guide wires, and provide movement in your neck. Overuse these muscles through misalignment or overload them, and they will become inflamed or tight, possibly pinching the nerves.

How to Safely Practice Headstand (Sirsasana)

Armed with this information, how can you incorporate sirsasana safely into your practice? Headstand or any posture for that matter doesn’t have to look like the pose in your yoga syllabus to start. Practice the actions of the pose in a modification, and you will receive more benefit than forcing the pose.

Here are some important points to practice sirsasana.

1. A strong headstand begins with sensible upright posture.

Carry your upper palate above your physical heart. Assume a natural lordosis in your neck. Your best posture will be your tallest, most easeful posture. Maintain this easeful alignment of your spine in upright yoga postures. If you don’t know what good alignment feels like upright, you won’t know what it feels like upside down.

Practice holding Tadasana in ideal alignment and full attention for several minutes. To simulate the postural muscles further, root down from the outer hips into your feet. Place a block on top of your head while standing, and root up into it from your upper palate as you gently resist. Breathe fully to expand and lengthen your torso. Drop your shoulders away from your ears, and slide the upper arms back to widen the clavicles (collar bones). Invite the ribs back, as this action tends to cause them to splay forward. Breathe into your back, particularly just above the waist.

Practice integrating your body from head to feet with these polar actions of rooting and lifting. When you are in perfect alignment, your body will feel like your favorite pair of walking shoes: No friction, no effort, just ease.

Which brings me to the next key.

2. Stretch your hamstrings and plantar fascia.

To get into any posture, the closer to ideal postural alignment you can get, the less likelihood of injury. To keep your neck safe in headstand, you need to be able to align your entire spine before taking away the support of your feet. In order to achieve this, the back of your legs and soles of your feet must be supple enough to walk into the posture without rounding the lower back and therefore the neck.

3. Apply the rules of progressive overload.

No one walks into a gym and does a clean and jerk with 150 pounds off the bat with no experience. So why would headstand be any different? The neck is accustomed to bearing a mere ten pounds of weight. Add resistance incrementally in weight and duration.

4. Create a stable foundation.

** **When you are ready to do sirsasana, interlace your fingers into prayer hands, with the exception of your pinky fingers. Your pinky fingers should be stacked, overlapping each other front to back. You should be able to see both middle fingers from above but not any of your palm to start–so slightly pronate your forearms. Once you tuck your head into your palms, the tendency is to roll onto the dorsum (back) of your hand. Starting in slight pronation will bring you into neutral alignment once you are in the posture. Now root down through parallel upper arms into the forearms, wrists and hands while keeping the spine neutral and your chest open. Nestle the back of your head into your hands. Distribute the weight between the crown of your head, forearms, wrists and hands.

5. Keep your mouth shut.

This one is mostly for teachers. Although designed primarily to aid in tongue movement and swallowing, the variety of muscles attached to the base of the tongue help to support your neck. Anchor the tongue to the roof of your mouth for additional stability. When it comes to standing on your head, recruit as much help as possible. So teachers, explain your demo first, and don’t speak once you are in the posture.

Precautions and Contraindications

There are precautions and contraindications to performing sirsasana, such as osteoarthritis of the C spine, any autoimmune disease affecting the musculoskeletal system, diabetes, heart condition, degenerated discs, down syndrome, or any other pathology affecting the neck.

However, even with these conditions, one can enjoy many of the benefits of the pose by simply embodying the actions of the pose in a modified form. With patience and keen attention, headstand can be performed safely to benefit your wellbeing.

Naomi Friesen possesses a deep understanding of the physical body through 20 years of teaching movement and anatomy. Students benefit from her knowledge of sound biomechanics by receiving safe and effective instruction. A personal trainer, pilates instructor and lifestyle/weight management coach for 12 years, she now teaches yoga after receiving her yoga instructor certification through Open Source Yoga School. Naomi’s intention is to facilitate connection for herself and students through yoga – connection to Source, connection between the parts of our body, our connection to others.

Website: www.victoriaschoolofyoga.com

Facebook: Victoria School of Yoga