Did Babylonians Discover Trigonometry 1000 Years Before the Greek?

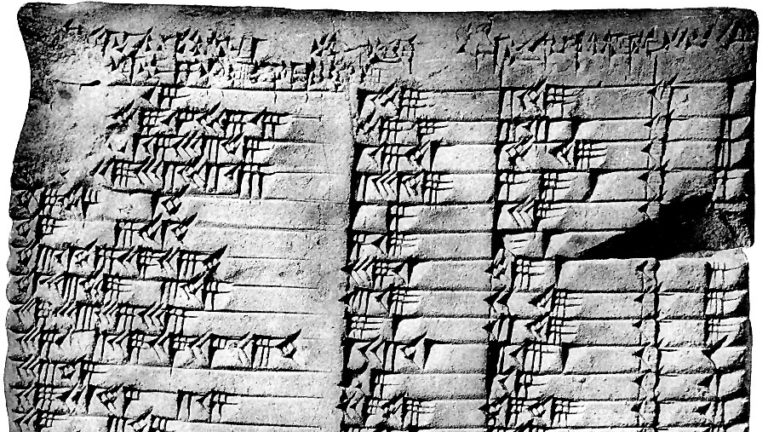

The dominant archeological perspective gives us a good baseline as to what our ancient ancestors knew, but every so often a discovery comes along that challenges those theories. We can thank the late, great journalist George Plimpton for one artifact that has recently challenged that narrative, potentially setting back the history of mathematics and casting a new light on the ever-intriguing culture of the ancient Babylonians. That artifact known as Plimpton 322, is a cuneiform tablet that was purchased almost a century ago from the real-life Indiana Jones, and could potentially prove that the ancient Babylonians were the first civilization to understand trigonometry.

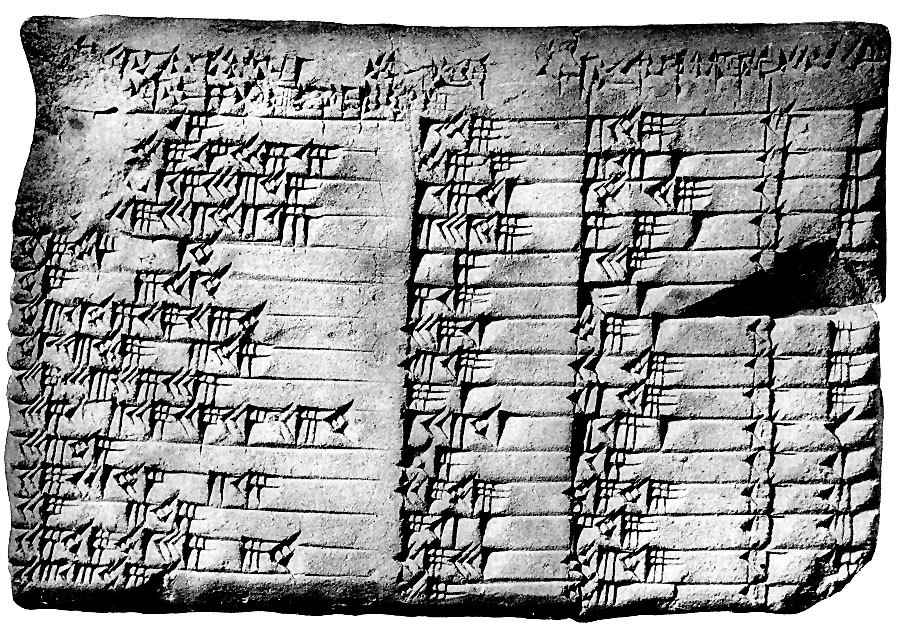

Cuneiform Tablets

Pythagoras is thought to have been the first to understand that the area of the square of the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares of its other two sides, a.k.a. the Pythagorean theorem. But it’s not necessarily well-documented that Pythagoras actually conceptualized this equation, nor are any other of his mathematical achievements.

Pythagoras ran a school that was shrouded in mystery and secrecy, with a kabbalistic take on math and numbers. Some believe it is possible that his students may have been responsible for his supposed achievements in mathematics but, due to either reverence or fear, gave credit to Pythagoras. Interpretations and documentation from the time are scarce, as knowledge was typically spread by word of mouth. At the same time, Pythagoras’ school was almost cult-like with stories of members being murdered for not maintaining the school’s secrecy and learnings.

The ancient Babylonians, on the other hand, used cuneiform tablets to record much of their intellectual work, with thousands of tablets having been recovered to this day. Many of them were excavated in the early 1900s and sold to museums or collectors, but some of the implications of their carvings are challenging what archeologists have believed about ancient history. One of these tablets was purchased by George Plimpton for a mere $10 in 1922 and has been the center of heated debate between archeologists. The new theory pairs the findings from Plimpton 322 with another tablet, known as YBC 7289, and posits that Babylonian mathematics included trigonometry, predating the Greek by 1,000 years. These ancient Babylonians used a base-60 system of mathematics rather than the base-10 system that we use today.

Plimpton 322 – wikipedia.com

While we have all assumed Pythagoras to be the first to postulate his eponymous theorem, Hipparchus is generally thought to be the Greek father of trigonometry and the first to produce a trigonometric table, known as the table of chords. Hipparchus’ work required a knowledge of trigonometry for measuring astronomical distances, but much of the basis for his work came from Babylonian mathematics using the base-60 system. Also, few details are known specifically about his life, despite being credited with the discovery of a large field of mathematics.

The base-60 system allowed the Babylonians to make trigonometric calculations in terms of ratios rather than angles. What is so fascinating about this discovery is that it brings a subjective interpretation to mathematics, which may seem counterintuitive. But the ancient Babylonian system of trigonometry shows that they were capable of achieving similar results using a different mathematical perspective. Part of their base-60, or sexagesimal system, is even retained today in certain elements of our lives like the number of seconds in a minute, the number of minutes in an hour, and the number of degrees in a circle.

Cuneiform Translations

Plimpton 322 was dated between 1822-1762 BC, around the rule of King Hammurabi, and contains a reference chart with four columns and 15 rows, laying out a table of ratios of right-angled triangles. These triangles range in proportion from nearly a square to a near flat line. The table is thought to have been used for construction purposes and could provide insight as to how the ancient Babylonians were such skilled architects and engineers. The ziggurats, hanging gardens and novel urban planning of the ancient culture are signs of a mathematically adept civilization, so it should be unsurprising that they could have been the first to develop trigonometry.

Cuneiform is the oldest written language in the world, created by ancient Mesopotamian civilizations using wet clay that was etched into and then baked in the sun or ovens. Written in either Akkadian or Sumerian, the majority of these tablets were excavated by Edgar J. Banks who was an archeologist and antiquities dealer, also thought to be the archetype for the character of Indiana Jones. Banks is thought to have uncovered and sold thousands of cuneiform tablets toward the end of the Ottoman Empire. The one sold to Plimpton however, has been one of the most controversial, regarding its implications on the history of trigonometry, while thousands of other tablets remain in private collections and museums that could shed further light on the subject.

Plimpton 322 was excavated in what would have been the ancient city of Larsa and was originally thought to be a scribe’s tally sheet or inventory report for transactions at a marketplace. If the cuneiform translations of Plimpton 322 as a trigonometric table are true however, they would not only change the study’s provenance, but also be considered the world’s oldest completely accurate trigonometric table. If this is true it would add yet another layer of profound sophistication to an already oddly advanced ancient civilization.

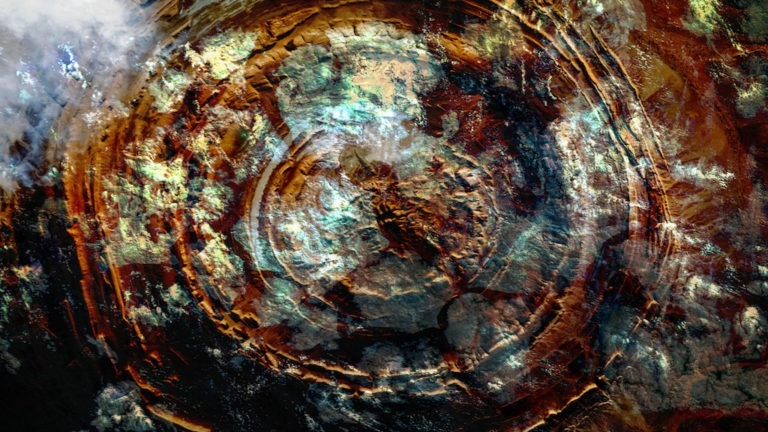

Has the City of Atlantis Been Discovered in the Eye of the Sahara?

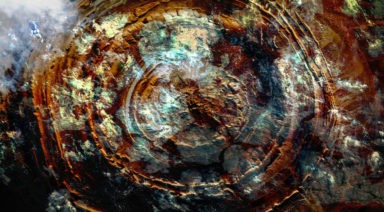

If you feel challenged by our relatively unconscious society, you may be one of the many dreamers who fantasize about the lost city of Atlantis. Some believe the Eye of the Sahara in Mauritania holds the secrets we’ve long imagined to be true. Stretching 14.6 miles across, the Eye appears to be from another world. Considering Plato’s writings on the subject, it’s possible this incredible structure is the final resting place of millions of Atlanteans.

While Plato’s descriptions of Atlantis are epic and mind-blowing, many believe he barely scratched the surface. He described Atlantis as a massive formation of concentric circles, alternating between land and water, similar to how the Eye is seen today. He emphasized that Atlantis was a wealthy, utopian civilization that created the basis for the Athenian democratic model. Plato then described the land as rich in gold, silver, copper, other precious metals, and gemstones.