Ancient Protection: Using Apotropaic Magic to Ward Off Evil

Ancient cultures regularly called upon the powers of magical, or apotropaic, symbols and rituals to guard them and their loved ones from evil. While some of these images seem to have faded into obscurity, one can still find them in their various forms — especially in the United Kingdom — often hidden in plain sight.

“Apotropaic” is derived from a Greek word, meaning “to ward off” or “to turn away,” and when applied to magic, it becomes an umbrella term for various symbols used on a house to keep evil from entering, as well as specific objects imbued with magical powers that protect those wearing or traveling with them.

Traditionally found engraved or etched onto, or burned into areas of entry, — especially windows, fireplaces, and doors — apotropaic symbols are seemingly commonplace on ancient buildings with inhabitants who were fearful of evil spirits. Those interested can find them on houses, barns, churches, and cellar doors.

In February 2019, the largest discovery of British apotropaic marks was made during one of many tours in Creswell Crags, a limestone gorge replete with cliffs and caverns. Here, one can get a feel for the way caves were used during the Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Roman ages. More than 100 of these so-called witches symbols were found, covering the walls and ceilings of the gorges’ numerous caves, and etched over dark holes and large crevices.

More than 50,000 visitors a year tour Creswell Crags, now considered a world-renowned heritage site. Until late, these medieval symbols were dismissed as common graffiti, but now experts claim that the scrawls are “actually the work of locals who once believed the ominous deep openings were a gateway to the underworld. The etchings were an apparent attempt to keep devils, witches and other evil occupants from spilling out.”

Lines and Shapes

Apotropaic symbols were most commonly created in three forms: a circle, a pentacle, and a “VV” shape. Less frequently, they have also found in diagonal lines, boxes, and mazes — and as hundreds of other variations on these themes.

The Daisy Wheel, or flower of life — a symbol resembling an encircled six-petaled flower — was the most frequently used witches’ symbol. Its single, continuous line was believed to be followed by evil spirits, and was used to confuse and trap them. Two small daisy wheels have even been discovered by the door leading into a beer cellar at Shakespeare’s birthplace at Stratford-upon-Avon, and many are still to be found in surviving English churches, as well as in medieval houses and farm buildings.

Daisy wheels inscribed at Bradford-on-Avon via historicengland.org

While the pentacle symbol is presently associated with paganism, it was regarded as the opposite in the Middle Ages— a mark imbued with the power to ward off witches. The five points on these stars were believed to represent the five wounds of Christ, and pentacles were most often worn as protective charms rather than etched into buildings.

In addition to designs, various letters are still believed to have significant power, depending on their associations. Most popular at the pinnacle of apotropaic usage was the “VV,” thought to evoke the protection of the Virgin of Virgins, or the Virgin Mary. Variations on this symbol appear as well, including “AM” for “Ave Maria,” and “M” for “Mary.”

In an era before scientific materialism, inhabitants of medieval villages attributed sickness, crop failures, and an array of misfortunes to the mischief of evil spirits — witches, demons, the devil, and so forth.

“Witches’ marks are a physical reminder of how our ancestors saw the world. They really fire the imagination and can teach us about previously held beliefs and common rituals. Ritual marks were cut, scratched or carved into our ancestors’ homes and churches in the hope of making the world a safer, less hostile place. They were such a common part of everyday life that they were unremarkable and because they are easy to overlook, the recorded evidence we hold about where they appear and what form they take is thin.”

– Duncan Wilson, Chief Executive of Historic England

What are now considered eerie and curious representations of a bygone era of a superstitious people, apotropaic symbols continue to resonate with people who profess a profound connection with the unseen world.

Apotropaic symbols may have grown out of popular favor, but their use is far from extinguished. While it may be difficult to assess the exact number of witches and pagans in the modern era, researchers from Trinity College conducted three surveys from 1990 to 2008 and found that, while there were an estimated 8,000 Wiccans in 1990, that number grew to 340,000 in 2008. Many of these individuals still use apotropaic symbols in their rituals and sacred texts.

Want to learn more about ancient signs and symbolism? Check out our series Secret Life of Symbols with Jordan Maxwell:

The Story of Atlantis, the Lost City

The history of Atlantis, with its sophisticated society and its tragic disappearance, has been the subject of study and fascination for centuries. In the series Initiation, Matias De Stefano offers a detailed and in-depth look at the evolution and impact of this lost city. In this article we explore the origins, structure, beliefs and fall of Atlantis, based on the accounts and knowledge shared by Matias.

Table of Contents

- The Origins of Atlantis

- The Structure of Atlantis

- Their Spiritual and Religious Beliefs

- The Heyday of the Atlantean Empire

- The Fall of Atlantis

- Khem: The New Atlantis

- The Legacy of Atlantis

The Origins of Atlantis

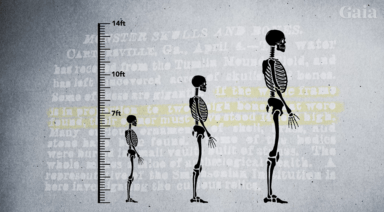

The story of Atlantis begins with the arrival of the Anunnaki, giant beings from the Middle East, who settled on Earth to help their species survive while their own planet was dying. These extraterrestrial beings had children with humans, creating a new civilization that would eventually become the Atlanteans. This mixing of races allowed the Atlanteans to inherit advanced knowledge and skills from the Anunnaki.

The Greek god Poseidon, known to the Atlanteans as Talyn, was one of these Anunnaki. Talyn protected and guided twelve of these mixed-race children, leading them from their isolated civilization in the Middle East to the Atlantic Ocean, away from the dominating influence of other Anunnaki. This established the twelve families of Atlantis, each charged with preserving and transmitting the star information they possessed.

The twelve families of Atlantis divided the main island into twelve small regions, each controlled by a family. These were not traditional rulers, but guardians of cosmic information. Through their connection to the stars, the Atlanteans developed a civilization that valued both spiritual knowledge and technological advancement.

The purpose of Atlantis was to be an experiment in human evolution, run by star beings such as the Arcturians and Pleiadians. These beings taught the Atlanteans to use sacred geometry and cosmic energies to build structures that were not only architecturally impressive, but also spiritually potent. These practices enabled the Atlanteans to achieve high levels of consciousness and wisdom.

In the series Initiation, available on Gaia, Matias De Stefano explores these origins in depth, revealing how ancestral knowledge and connection with beings from other dimensions shaped the advanced civilization of Atlantis.

The Structure of Atlantis

The structure of Atlantis stood out for its advanced organization and the integration of spiritual and technological principles in its urban and social design. The following are the most relevant aspects of this civilization:

- Regional distribution: Atlantis was divided into twelve regions, each governed by one of the twelve families. These regions represented not only administrative divisions, but also areas of spiritual and technological responsibility.

- Spiritual rule: The twelve families that ruled Atlantis were not monarchs in the traditional sense, but guardians of cosmic wisdom. Their leadership was based on spiritual knowledge and ethical guidance rather than authoritarian control.

- Circular city: The capital of Atlantis was a circular city located on the main island. This layout reflected the harmony and balance that the Atlanteans sought in all aspects of their lives.

- Resonance technology: The Atlanteans used vibration and sound technology for building and healing. This technology allowed the construction of pyramids and temples that acted as resonance points for communication and energy transfer over great distances.

- Sacred geometry: Atlantean architecture incorporated principles of sacred geometry, using shapes and patterns such as the Flower of Life to align their structures with cosmic energies, facilitating meditation and spiritual connection.

- Portal network: Atlantis had a network of natural and artificial portals that allowed the connection with other dimensions and the transfer of cosmic information. This network was fundamental for its spiritual and technological evolution.

- Wisdom centers: Temples in Atlantis served as places of knowledge and energy. They were designed to optimize energetic resonance, facilitating advanced spiritual practices and connection with cosmic forces.

- Stellar influence: The knowledge and skills of the Atlanteans came from their interaction with beings from other worlds, such as the Arcturians and Pleiadians. This interaction profoundly shaped their culture, religion and technology, integrating cosmic knowledge into their daily lives.

- Strategic expansion: During their heyday, the Atlanteans established settlements in key regions such as Egypt and the Mediterranean. These settlements not only expanded their territorial influence, but also allowed them access to important energy portals around the world.

Their Spiritual and Religious Beliefs

The spiritual beliefs of the Atlanteans were deeply rooted in an understanding of the connection between the cosmos and life on Earth. They believed that all divinities were different expressions of a single universal consciousness. This approach allowed the Atlanteans to see every aspect of nature and the cosmos as a divine manifestation. Natural elements such as water, fire, earth and air were considered sacred, and each had its own gods and guardian spirits. This worldview fostered a deep respect for nature and the interconnectedness of all life.

One of the pillars of Atlantean spiritual beliefs was the practice of sacred geometry. Atlanteans used specific shapes and patterns, such as the Flower of Life, to align their structures with cosmic energies. They believed that these geometric shapes were the key to understanding and manipulating the energies of the universe. Temples and other important buildings were built according to these principles, allowing the Atlanteans to create spaces that facilitated meditation and spiritual connection.

Atlantean rituals and ceremonies were designed to maintain balance and harmony at both the individual and collective levels. They used vibration and sound to heal and elevate their consciousness, integrating practices such as chanting and harmonic resonance. These ceremonies not only strengthened the community, but also served as a means to align with cosmic forces and receive spiritual guidance. This holistic approach to spirituality allowed Atlanteans to live in harmony with the universe and foster continued spiritual growth.

The Heyday of the Atlantean Empire

At its peak, Atlantis had a population of approximately 300,000 people distributed in several villages along three main islands. This distribution reflected the advanced organization and planning of the Atlantean civilization.

The Atlantean empire reached its greatest expansion by establishing settlements in the Mediterranean and beyond. Following Earth’s energetic patterns, the Atlanteans founded colonies in regions such as Egypt, Asia Minor and the Middle East. These settlements not only extended their territorial influence, but also allowed them access to important energetic portals that strengthened their connection to cosmic energies. Atlantean expansion was both a territorial conquest and an effort to unify the planetary energies under their control.

Atlantean technology played a crucial role in their heyday. They used vibration and sound to build and heal, developing a network of pyramids and temples that functioned as resonance points. This network allowed the Atlanteans to communicate and transfer energy over great distances. In addition, this technology was used for cell regeneration and life extension, demonstrating their mastery over natural forces and their ability to manipulate physical reality.

The Atlantean system of government was based on wisdom and spiritual guidance. The twelve families that ruled Atlantis were not tyrants, but guardians of cosmic wisdom. Their leadership was focused on maintaining balance and harmony in society, using their knowledge of the stars and sacred geometry to guide the civilization toward sustainable and spiritually advanced development. This approach allowed Atlantis to flourish as a prosperous and balanced civilization, capable of integrating advanced technology with deep spirituality.

The Fall of Atlantis

The fall of Atlantis is one of the most tragic and fascinating stories of antiquity. The Atlantean civilization began to disintegrate during the Age of Scorpio. This period was marked by an abuse of the knowledge and technology possessed by the Atlanteans. The leaders of Atlantis, once guardians of cosmic wisdom, began to use their abilities to exert power and control over others, deviating from their spiritual and ethical principles.

This abuse of power led to a series of natural catastrophes that contributed to the destruction of Atlantis. The Atlanteans had developed advanced technologies that used frequencies and resonances for multiple purposes. However, these same technologies were employed for war and domination, resulting in devastating energy waves that caused the disappearance of entire cities and turned fertile regions into barren deserts.

Internal tensions and conflicts with other civilizations also played a crucial role in the fall of Atlantis. The war with the civilization of Mu was especially destructive, leading to a series of battles that depleted Atlantean resources and morale. Finally, a combination of natural disasters and internal social collapse culminated in the complete destruction of the Atlantean civilization, with the main island sinking into the ocean in a single night of misfortune.

Khem: The New Atlantis

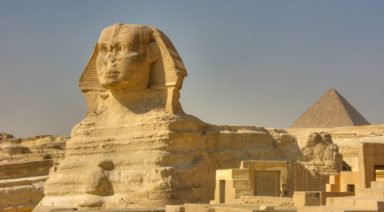

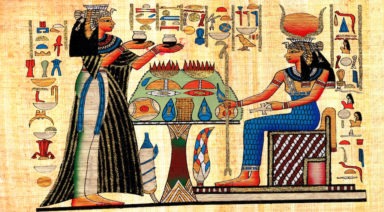

Khem, known as the new Atlantis, emerged after the collapse of the Atlantean civilization. This transition occurred during the Age of Virgo, when the remaining Atlanteans migrated and established new bases in Egypt and other regions of the Mediterranean. Khem inherited much of Atlantean knowledge and practices, including the use of sacred geometry and vibrational resonance in their constructions. The temples and pyramids of Egypt bear witness to this transfer of wisdom, which continued to influence the spiritual and technological development of the region.

The new civilization of Khem focused on maintaining and expanding Atlantean knowledge, adapting it to its new environment. This integration allowed Khem to flourish as a center of learning and spiritual evolution. Khem’s leaders, many of them descendants of the ancient Atlantean guardians, worked to preserve the harmony and balance that once characterized Atlantis. Thus, Khem became a bridge between the legacy of Atlantis and future civilizations, ensuring that the lessons learned would not be lost to time.

The Legacy of Atlantis

Despite its destruction, the legacy of Atlantis lives on in numerous cultures and traditions around the world. The teachings and technologies of the Atlanteans were carried to new lands by their survivors, influencing regions such as Egypt, Greece and Central America in their mythology, architecture and spiritual practices. These cultures reflect Atlantean knowledge of sacred geometry and cosmic alignment in their monuments and temples.

The spiritual impact of Atlantis is also evident in many religions and esoteric philosophies. The principles of connection to the cosmos, the importance of energetic alignment, and the use of vibration and sound for healing and evolution are concepts that have endured throughout the centuries. These teachings continue to inspire spiritual seekers and modern practitioners who seek to integrate these principles into their daily lives.

In addition, the story of Atlantis has been a catalyst for exploration and the search for lost civilizations. Archaeologists, historians and explorers have dedicated their lives to unearthing the remains of this ancient civilization, searching for evidence to corroborate the accounts of Plato and others. These efforts have led to numerous important discoveries that have enriched our understanding of ancient cultures and their connection to Atlantis.

The story of Atlantis continues to be a source of inspiration and reflection on human potential and our capabilities. It reminds us that while we can reach great heights of knowledge and technology, we must do so with a sense of responsibility and ethics. The legacy of Atlantis urges us to learn from its mistakes and use our abilities to create a more harmonious and balanced world, avoiding the paths that led to its downfall.