The Yoga Pose You’re Doing Wrong (and How to Modify it Safely)

Take any yoga class and it’s almost guaranteed that you’ll do downward facing dog, or adho mukha svanasana, at least once. If you’re a fan of flow classes, the amount of times you’ll find yourself in down dog increases exponentially. For beginners, despite their teacher’s touting down dog as a pose of rest, it feels less like rest and more like a full body workout. This isn’t exactly untrue. When downward facing dog is executed properly the core is engaged and the entire back body is stretching, with the arms bearing some of the body’s weight, making down dog a pose that works the entire body from hands to heels. A correctly executed down dog also has many physical and mental benefits, including building bone density, increasing circulation, developing flexibility, calming the mind and counteracting fatigue. But when done wrong the benefits of the posture may be lost and put the yogi at risk for injury, especially if they’re hitting downward facing dog repeatedly.

Most of the students I see in class doing down dog incorrectly are making the same mistake. They slump forward into their shoulders, hunching their upper back and misplacing the majority of the weight from their trunk and hips into their shoulders and wrists. The shoulder, a ball and socket joint, is a shallow joint with a complex network of muscle and ligament attachments. This gives the joint a lot of flexibility but also increases the risk of injury, especially dislocation or wear and tear injuries involving the rotator cuff. Shoulder injuries can be extremely painful, and in some cases, can become chronic problems. Because of the complexity of the shoulder’s structure and a modern lifestyle that doesn’t always encourage strong muscle development in the area, shoulder injuries can be hard or impossible to repair, even with surgery. This makes properly practicing poses where the shoulder can be vulnerable, such as down dog, extremely important. Yoga is supposed to make us feel good inside and out, not leave us with chronic pain.

So how do you know if you are doing down dog correctly? First and foremost, listen to your body. If you are feeling discomfort or sensations that don’t resemble the description above, chances are something is off. Are the heels of your hands digging uncomfortably into the ground? Do your shoulders feel heavy and seem to sag toward your ears? Is there little to no feeling of stretch happening throughout your back or hamstrings? Does it feel as though your back is curving upward, like it does during cat pose? These may be signals that you need to make adjustments.

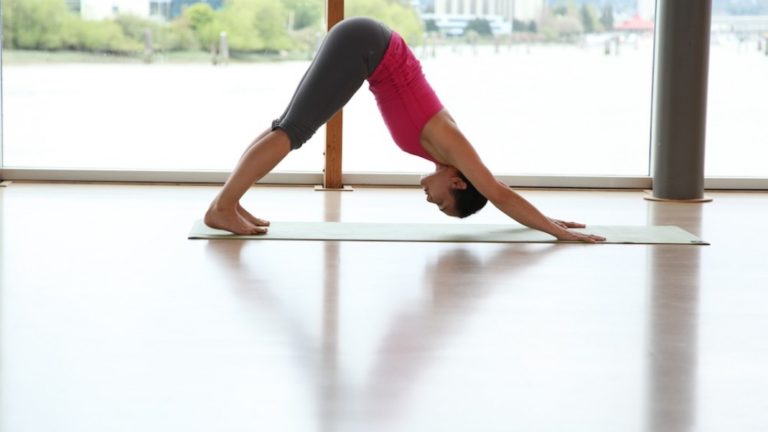

In a proper down dog the base of the pointer and pinky fingers and the heel of the hand should be pressed firmly into the mat. The arms should feel engaged, long, and be externally rotating, with the bony part of the elbows tracking backwards toward the body, rather than facing outwards. The shoulders should be pushing back from the ears with the shoulder blades pressing flat to the ribs. The back body should feel long and flat. The hips should continue this line, so that the entire top half of your body creates a long line from the base of the hands to the tailbone. The legs should feel a stretch through the hamstrings, with the knees straight, but not locked, and the heels pressing toward, or onto, the mat. The feeling should be of the thighs pressing back away from the arms. The lower half of the body is ideally a long line from hip to heel. The entire pose should look like two lines forming an inverted “V”.

Aren’t there exceptions to every rule? Isn’t a yoga practice about showing up and working to your level, rather than striving for the perfect posture all the time? Absolutely. But there is a difference between working on a posture where you are at, and working on a posture unsafely, even if you aren’t striving to put your body into a pose it isn’t ready for. As practitioners, part of being accountable for our practice is seeking guidance when something doesn’t feel right for our bodies. This goes beyond listening to descriptions or corrections given out in class. It means remembering that being pro-active can save us from unnecessary injury or chronic pain. If your down dog doesn’t seem quite right, an experienced teacher can provide you with the guidance to modify it to suit your body and practice while allowing you to safely reap the benefits of the pose.

3 Yoga Poses for Labor

As a birth doula and yoga teacher, I believe that yoga for labor is one of the most rewarding forms of yoga. Your labor could be a breeze or it could be a marathon. Either way, these sure fire hip-openers can help give you the edge.

(Click here for prenatal yoga videos.)

1. Cobbler’s Pose/Butterfly.

Take your Cobbler’s Pose to new heights by not only lengthening and strengthening your upper back, helping to improve your posture, but the lift also allows the hips to fall open towards the sides, going deeper into your groin muscles and stretching the pelvis to open for birth. Place the soles of the feet together in front of your body and walk the hips back an inch to rest in a forward pelvic tilt. Keep the outer edges of the feet pressed to the earth as you roll your shoulders open and back and lift your hips from the floor

- enjoying a deep stretch in the entire back from crown to tailbone.

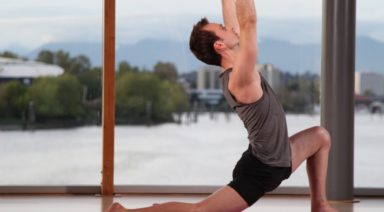

2. Low Lunge Pose.

Lunge is a terrific pelvic floor stretch as well as a strengthener for your thighs. In addition, it stretches the hip flexors which lead into the back and can alleviate some of the tension in your tight lumbar. I often recommend my Doula clients to try this pose while standing in labor, as it may help to open up the pelvic floor on one side more than another, which is useful for babies who like to thumb suck in utero and cannot descend with a little arm in the way!

3. Downward Facing Dog.

The Downward Facing Dog is a standard pose in most classes, but done properly with birth in mind, can also become your new best friend. Begin the pose by sitting on the heels with the arms outstretched on the mat as far in front of you as you are comfortable. Keep the fingers soft and the shoulders pulled into the back with a long neck. Shift your weight into your toes and lift the knees slightly from the floor. Keep reaching with your chin as you straighten the legs, letting the heels descend, and the shoulders pulled back into the spine. The head will naturally fall towards the floor as your hips elevate, keeping the length and the strength in the shoulders behind you, where it belongs. As you lift the hips, lift the tailbone and stretch the hamstrings from heels to hips forming a perfect triangle with your body. In this position, the baby can fall out of the hips and low back, offering relief in later weeks as well as encouraging a breech baby to shift with the relaxation of the internal ligament structure.

*Consult with your medical professional before starting any new physical regime during pregnancy or labor.