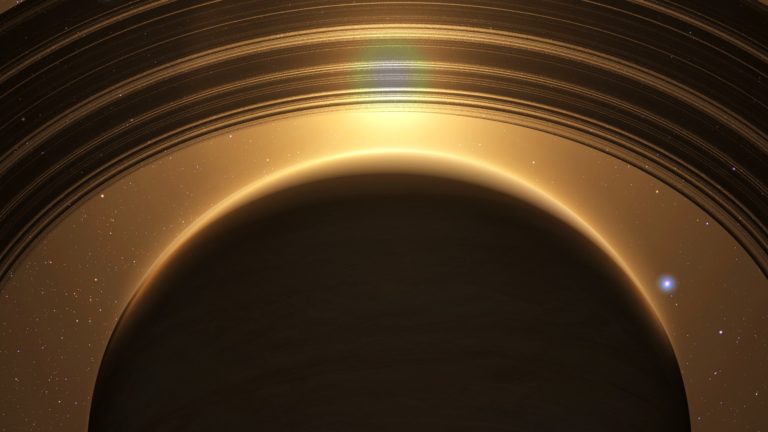

Glitch Discovered In Saturn’s Rings By Cassini Spacecraft Images

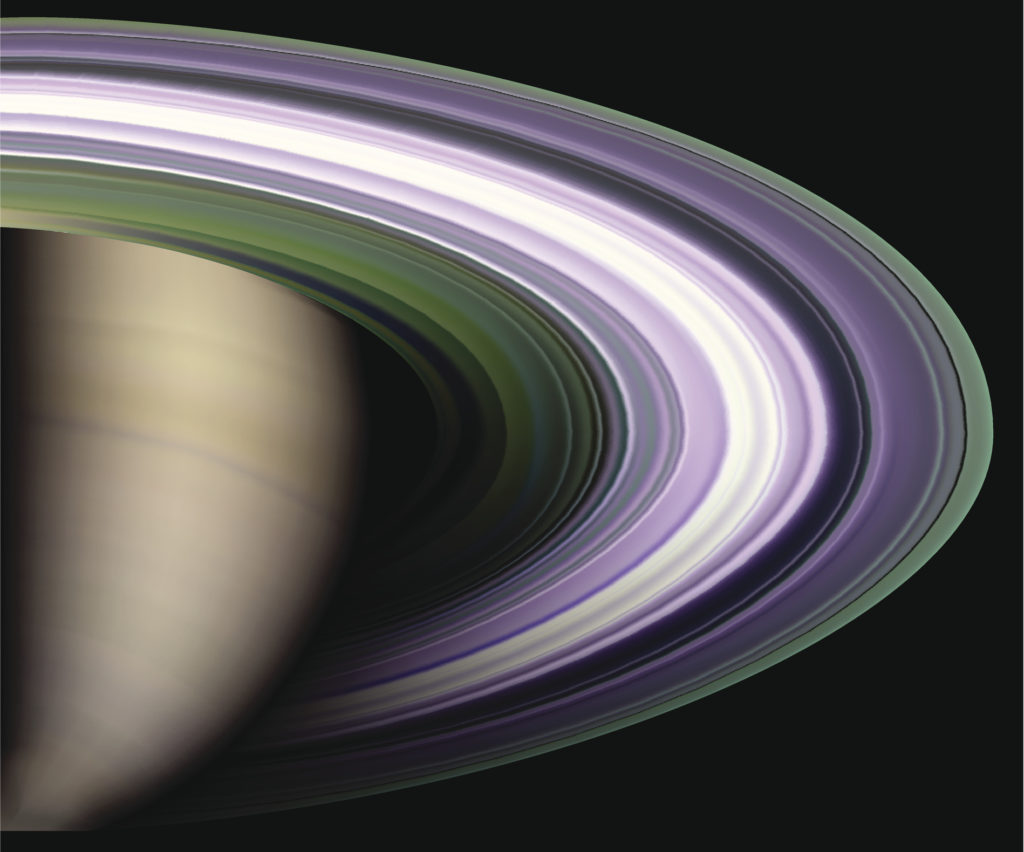

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft recently ended its 20-year mission to Saturn. It was the first spacecraft to ever orbit the massive gas giant to study the planet’s myriad features, such as its extensive system of rings. These seemingly perfect bands of ice and rock had been photographed before and were thought to be mostly understood by astronomers, until Cassini found a rare exception: A glitch on the outer edge of the planet’s A-ring.

Is Peggy Just a Moonlet?

Launched in 1997, the Cassini spacecraft has always been on a suicide mission, albeit one filled with scientific discovery. That mission lasted just under 20 years, and its final days resulted in some of the most exciting images of the second largest planet in our solar system. The spacecraft discovered two new moons, deployed a probe that landed on Titan, and slipped between two layers of rings in its orbit.

Over its 10-year orbital period, images from Cassini began to show something that has still gone unexplained, a glitch in one of the rings. This glitch was first discovered by a long-time member of the imaging team, Carl Murray, who named it after his mother-in-law, Peggy, whose birthday it was.

When first imaged in 2013, Peggy was about 1.5 miles wide, and imperfect compared to Saturn’s otherwise pristine circuits. Because of its tiny size, the Cassini spacecraft was unable to capture it in great detail or within close proximity, but it was enough to recognize its anomalous nature. Murray and his NASA colleagues said they believed Peggy to be either a moon in the making or a moonlet disintegrating, as she got smaller during future imaging.

nasa.gov

Saturn’s rings consist of countless particles of ice and rock that orbit within the Roche Limit, an area where the planet’s gravitational force becomes so strong it rips apart small celestial bodies, such as asteroids and meteors. Typically, these particles will coalesce to form moons, but Saturn’s pull prevents this, instead maintaining their orbit. These small lunar building blocks are sometimes referred to as moonlets.

At first, scientists believed Peggy might have been a full-fledged moon, disrupting the flow of Saturn’s orbiting moonlets, but this theory was discounted because they would have expected it to create more chaos.

According to NASA, it has been difficult to track Peggy, as she’s not always been where they expect her to be. And though scientists believe Peggy may have been a nascent moon at one point, she still remains within the not-fully-explained category of Saturn’s features.

Strange Features In Images From Cassini Spacecraft

The Cassini spacecraft gave us quite a bit of new information about Saturn’s many moons, including the fact that some of them could potentially support life. The Huygens probe, carried by the Cassini spacecraft, landed on Titan, a moon with a significant amount of surface water.

Another of Saturn’s moons, Enceladus, is thought to contain vast oceans beneath a layer of ice on its surface. These discoveries have raised the question of whether there is a possibility of life on these moons, as well as some other interesting theories.

The most unusual moon in Saturn’s orbit is one known as Iapetus. This walnut-shaped satellite has some odd features which some believe are characteristic of an artificial satellite. One half of the moon is bright white, while the other side is dark black with almost no reflectivity. There is a ridge running along its equator that alternative theorists have likened to two independent half-shells welded together. Others have imagined it to possibly be a wall of sorts.

Some have pointed out that it’s odd shape resembles a dodecahedron, evidence of artificial construction compared to the more spherical shape of natural satellites. Further study of Iapetus’ lunar surface shows additional geometric features with lines just a little too straight to be the product of natural mechanisms.

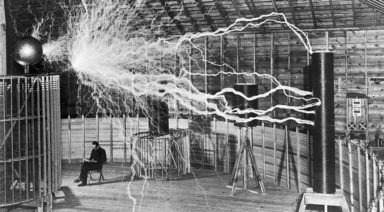

David Icke has proposed the idea that Saturn’s rings are actually artificial, based largely on a book titled Ringmakers of Saturn. He says he believes that Saturn is a broadcasting system, amplifying a frequency that is directly tied to our perception of reality. He points to the similarity between the rings of Saturn and information encoded on a CD or DVD.

Icke says he believes this signal is malevolent and that it’s broadcasting a false reality. He says these satellites orbiting Saturn are electromagnetic vehicles creating the rings, and that one can see exhaust being emitted in the process. Icke says he believes Saturn used to be a star like the sun, but that it is now being used to resonate sound frequencies.

There are, in fact, strange radio signals being broadcast from Saturn which can be found on NASA’s website. Could these eerie tones, that sound like something straight out of a horror movie, actually have an effect on Earth and our consciousness?

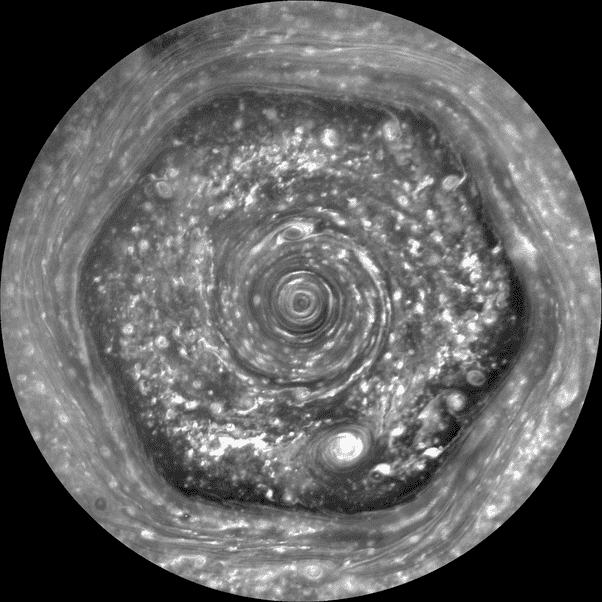

Another bizarre discovery on Saturn that has puzzled scientists and alternative theorists alike, is the massive hexagonal storm on the planet’s north pole. This storm stretches over 20,000 miles wide and reaches down at least 60 miles into the planet’s atmosphere. Its distinctively straight sides show how the winds in this gaseous storm shift direction drastically, a phenomenon never observed before.

David Wilcock draws the connection between the storm’s shape and Hans Jenny’s discovery of colloidal suspension. Jenny showed the way that sound frequencies create geometric patterns in solutions where particles are suspended in water and gas.

Could there be a connection between Icke’s theory of Saturn as a frequency transmitter and this massive hexagonal storm on the its north pole?

Professor Predicts Binary Star Collision Will Light Up Night Sky

In 2022, a binary star system will merge creating a massive explosion visible from Earth by the naked eye. Astronomers say this stellar collision in the Cygnus system will create what’s known as a red nova, in the first ever predicted collision of a binary star system.

These stars, known as KIC 9832227, are an eclipsing system, meaning they’re locked in a cosmic dance around each other, observed to have grown shorter over the past five years. The stellar companions were first observed by Calvin College professor, Lawrence Molner.

Molner is monitoring the system with a low budget and relatively small telescope to predict the stars’ collision. He says typically observations of this magnitude involve billions of dollars and teams numbering in the thousands. But rarely will a phenomenon such as this achieve that level of funding, due to the low probability of prediction accuracy.

“It’s a one-in-a-million chance that you can predict an explosion,” Molner said. “It’s never been done before.”

Though binary mergers like this have been observed before, it’s usually after the fact. If Molner’s prediction holds up it will be a first. The only other red nova to have been observed after a collision was by astronomer Romuald Tylenda, in 2008.

When the two stars eventually collide, they will produce what’s called a luminous red nova – an explosion that releases energy tantamount to all of the energy our sun will release in its entire lifetime, and it will be visible without a telescope for up to a month.