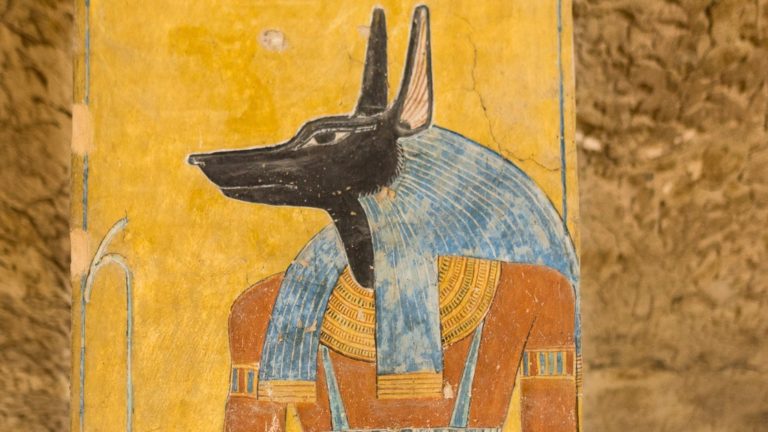

Anubis: Egyptian Dark Lord of the Abyss

Among the first of all Egyptian Gods, Anubis the jackal emerged in Egypt’s ancient mythology before the First Dynasty (c. 3150–2890 B.C.E.). The jackal god witnessed the rise and fall of pharaohs, protecting them as they shed their mortal coils and crossed to the underworld. Surprisingly, Anubis, one of the most prevalent mythological figures of Ancient Egypt, did not have his own temple. His striking image is found in figurines, statues, and hieroglyphs, and portrayals are ubiquitous in tombs, cemeteries, and books of mortuary rituals (such as the Book of the Dead).

The earliest records of Anubis show that he was revered as the King of the Dead, and is even more significantly regarded than Osiris, who was later introduced into Egyptian mythology as Anubis’ father. Osiris assumed the title “God of the Underworld,” stripping Anubis of his prestige, then overtook him in importance during the Middle Kingdom period (2040-1782 B.C.E.).

Anubis thereafter came to be known as Osiris’ assistant in the underworld and protector of his tomb in the mortal world. Even so, the jackal god remained a top-tier deity with numerous grave responsibilities for the dead.

A Gnarled Family Tree

There are a few different stories of Anubis’ origin, but the most popular tells of his birth to Nephthys, a goddess who represented protective guardianship and was known as a “Friend to the Dead,” and Osiris, the god of the underworld. Nephthys was married to the god Set, for whom she had little use or affection. She did, however, have feelings for Osiris, who was married to her twin sister, Isis. As the myth goes, one fateful night Nephthys posed as her sister, plied Osiris with alcohol, and then seduced him. As a result of their union, Anubis, the funerary God, was born.

The Powers of Anubis

In perhaps the most well-known ancient Egyptian myth, Set, angry that Osiris had relations with his wife, sought revenge. He eventually found Osiris, killed, and dismembered him, and flung the 14 pieces of his body into the Nile. Isis organized a search party of scorpions, her sister, and Anubis, but were only able to find 13 pieces of Osiris’ body.

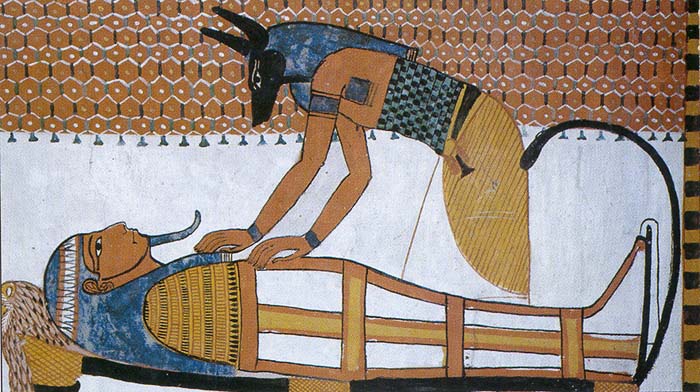

She reconstructed the final part with her powerful magic. The story of Isis miraculously reassembled her husband became legendary, and Anubis was credited with inventing mummification to preserve his body. With this act, the jackal god secured his role as the patron god of embalmers. For this reason, illustrations in the well-known Egyptian Book of the Dead depict priests wearing jackal masks when conducting funerary rites.

After the death of Osiris, Anubis became his father’s right-hand assistant in the underworld as well the world of pharaohs, queens, and mortals. With his expertise and knowledge of preserving the dead through mummification, Anubis was highly revered as their protector.

Anubis Reconstructing Osiris: 1350 BC, Tomb of Ramses I, Egypt

Whenever a mortal passed into the underworld, Anubis led the soul to the Hall of the Two Truths, where he would then decide the fate of the soul. He was thus also known as “The Guardian of the Scales.” The Book of the Dead shows Anubis acting as a judge, weighing a person’s heart on a set of scales, against a feather of truth. Those who had earned eternal life were led to heaven; the condemned were devoured by Ammit, the goddess of retribution.

An amorphous character, Anubis was not only associated with embalming and death but also with secrets beyond the ken of human beings, as he was well-versed in the mysteries of the afterlife. It was for his special knowledge that Anubis was perceived more as a trusted guide than as the taker of lives.

Notably, because of Anubis’ embalming skills, he was considered to have an exceptional understanding of anatomy, which led to his eventual role as the patron of anaesthesiology. His priests were also credited as being well-versed in herbal arts.

Symbolism of Anubis

As with any god, every aspect of Anubis’ appearance is symbolic. Most commonly depicted with the head of a jackal and the body of a muscular man, Anubis also appears as a jackal. In either form, his head is covered in black fur, which differentiates him from the carnivorous scavenger animal of the wild, with characteristically brown fur.

Black represents death, but it is also the color of rebirth in the afterlife, modeled after the Nile’s rich soil, which was then seen as a symbol of fertility. Anubis’ ears are always perked and alert — on guard and sensing any trouble afoot, beyond the range of human senses.

The reason the god of embalmment was depicted as a jackal is no more than an educated guess. It is thought, however, that the myth stemmed from early issues in keeping wild animals from feasting on the dead post-burial. Perhaps the early Egyptians believed a powerful jackal would be the best defense.

Anubis is also shown as having an Imiut fetish, which was thought to embody the magical powers of a spirit so that he could create a connection between the mortal world and the underworld. Imiut fetishes were buried in the tombs of dead pharaohs and queens — including those of Tutankhamun and Hatshepsut.

In some illustrations, Anubis poses with a flail, a crook, and a long pole (known as a was scepter). The flail, an agricultural tool, and a herding crook represented both the pharaoh’s role as provider and shepherd of his people. The was scepter, another magical fetish, symbolized the divine power of the pharaoh.

Anubis Knew Death Was Not the End

Since the beginning of humanity, there has never been a greater mystery to the mortal experience than death. And it seems that the ancient Egyptians, including the great pharaohs, placed as much interest in the afterlife as their daily existence. Anubis became the symbol of the great unknown, always present to usher the dead into the abyss beyond the mind and body. The striking figure of the jackal god has persisted through millennia like no other deity, etching a core belief into the rich history of an ancient civilization — that this fleeting life is but the beginning of a never-ending journey.

Amateur Archeologist Believes He Knows Location of Holy Grail

The search for the Holy Grail—has the ancient relic been located in England?

The Holy Grail is thought to have been the legendary cup of Christ used by Jesus at the last supper. Treasure hunters have searched for it for centuries, and hundreds of people have claimed to possess it. Now, U.K.-based amateur archeologist Barrie-Jon Bower, tells the Sun newspaper he knows where it is.

Bower, who says he has studied the grail and the Knights Templar for years, believes the grail is hidden in a secret chamber beneath a manmade river in the Hounslow Heath area of London. But how could one of the most sought-after relics of the holy land make its way to an underground hiding place in London? Bower tells the Sun that the Knights Templar trained in this area and claims they built this secret underground crypt to hide treasures from the holy land. Bower told the Sun, “[f]inally, I am certain this is the right spot. I am certain there will be a vault beneath the surface, with the Grail inside and other treasures from the Crusades.”