Understanding the Sacroiliac Joint

Asana Anatomy-Understanding the Sacroiliac Joint

Controversy does not often strike the yoga community. Non-harming, truthfulness, and loving kindness are not very controversial concepts. Yet the poor, barely mobile, sacroiliac joint has become the center of a yoga debate – to square or not to square the hips. Ok, so it is not as racy as a celebrity feud, but it may affect your personal yoga practice.

Let’s dissect this joint.

The two sacroiliac joints (SI joint) are formed by three bones: the triangular sacrum bone, and the two wing like bones of the pelvis known as the ilium. Each iliac bone (one half of the ilium) comes in contact with one side of the sacrum, forming two SI joints. This connection is like three puzzle pieces fitting together known as form closure. Form closure creates stability, keeping the pelvis together in one unit. The SI joint itself is shaped like a boomerang with two arms at 90 degrees to each other. The upper portion lies in an up-and-down orientation and the lower portion lies in a front-to-back orientation. The surface of the joint is covered in coarse cartilage, adding friction and contributing to the force closure.

The sacrum moves in nutation (forward) and counter nutation (backward) in relation to the ilium. The sacrum can move only on one side, like in lifting one leg, or both sides, like when we move from lying to standing. This movement is very small, amounting to 1 or 2 mm of motion in either direction. As we age, the sacrum becomes wedged increasingly forward, but this doesn’t fully happen until we reach our 30’s. This wedging increases the resistance to shearing (twisting) forces across the sacroiliac joint. Herein lies the problem. The SI joint is a joint that is intended to provide stability for the pelvis, and is not built to move.

The SI joint has another mechanism of stability – force closure. This is the stability created by the action of the core musculature that has attachments into the SI joint – namely, the muscles of the pelvic floor, and the transverse abdominis. Conveniently, we can access these muscles through the activation of the bandhas or energy locks in yoga. In mula bandha we imagine a subtle lifting up of the muscles we use to control the flow of urine. In women, activation of this musculature has been shown to provide force closure for the SI joint. In uddiyana bandha, we draw the lower belly in and up, activating the transverse abdominis muscle. For this version, the scooping of the lower belly needs only to be subtle, and slightly flattens out the lower abdomen.

Hip Opening or Sacroiliac Opening?

Many of us identify ourselves as having “tight hips”. For many, this means a lack of external (outward) rotation at the hip joint. Using the example of Virabhadrasana I or Warrior I pose, our front hip is in a flexed position with toes pointing straight ahead. Our back foot is on the floor at a 45 degree angle, and in order for the points of our hips (our iliac crests) to face toward the front of the mat, our back hip needs to extend, and externally rotate. If we look deep inside we see that these actions require our sacrum to nutate forward on the side of the lead leg, and counter nutate backward on the side of the rear leg. If the rear hip resists external rotation in order to square the hip points forward a twisting or shearing force is introduced across the SI joint. Over time this can lead to irritation, hypermobility, and dysfunctional firing patterns of our pelvic musculature.

Happy Sacrum

This situation is an opportunity to practice ahimsa or non-violence towards our SI joints. There are a few ways you can diminish the shearing force across the SI in standing poses. The first is to take a slightly wider stance, opening your feet to hip width (rather than heel to arch or heel to heel). This enables your pelvis to comfortably square forward. Another option is to keep the feet as they are and simply allow your pelvis to be slightly open to the side of your mat. That’s right, let go of the desire to perfectly square your pelvis forward. Instead, imagine the hip bone in its socket, outwardly rotating. Keeping that rotation, tuck the tailbone under slightly, creating room in the front of the hip. You may find that this provides more freedom of movement and may naturally square your hips further. In standing and seated twists, be sure to engage the muscles of the pelvic floor (mula bandha) to support the SI joint before twisting.

When we step back for a moment and acknowledge the true purpose of our yoga practice, suddenly trying to make our bodies fit a mold doesn’t make much sense. Being more forgiving and accepting of our bodies limitations enables us to go much deeper into our yoga practice and experience the joy of yoga safely. Now that doesn’t sound controversial at all.

Yoga Anatomy: Reducing Shoulder Impingement

![]()

![]()

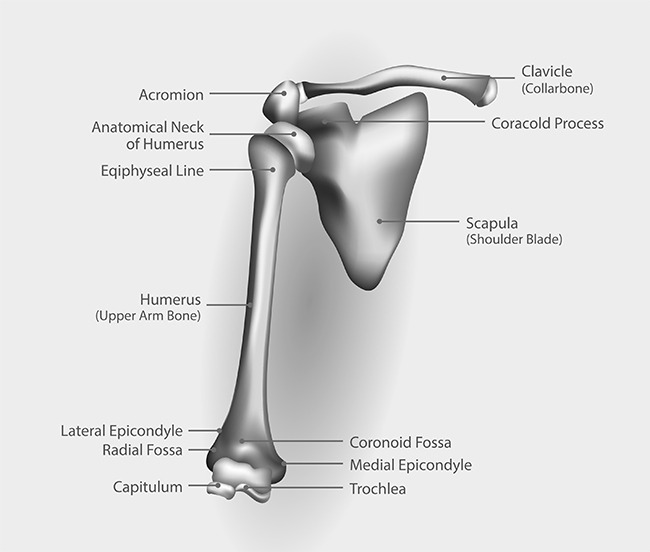

Our wonderful shoulders are the most mobile joints in the body and, for anyone who has done any amount of Hatha Yoga flow, we can appreciate how much the shoulders are engaged and challenged in our practices. Given how frequently we load and stress the shoulders in yoga, it is ideal to move the shoulders with intelligence, mindfulness, and attentive care. One aspect of mindful movement and engagement is reducing the onset of shoulder impingement.

Our shoulder joints are made from a ‘ball and socket’ design. The upper arm bone (humerus) has defined structures at its proximal end (closest point to the center of the body). At the proximal end of the shaft, we see that the humerus has boney processes (called tubercles where tendons attach). Moving towards the shoulder joint, the humerus has a neck that transitions into a ‘head’ or the ball portion of the joint. The humeral head inserts into the socket (glenoid fossa or cavity) forming this highly moveable joint. The socket is part of the shoulder blade (scapula bone). There is another part of the shoulder blade with a boney projection called the acromion process which is positioned above the humerus. You call feel the acromion process on yourself by taking one hand over and to the back of the shoulder blade. Run your fingers along the shoulder blade to find a horizontal line of bone – this the spine of the scapula. Run your fingers all the way to the end into your shoulder – where this ends is your acromion process.

Between the acromion process and the tubercle region of the humerus is the ‘subacromial space.’ This is where our attention goes regarding shoulder impingement considerations. Deep above the spine of the scapula runs one of your rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus muscle), which has its tendon traveling through the subacromial space and attaching onto the greater tubercle of the humerus. To offer some protection to this tendon, there is a small sac of fluid (bursa sac) between the tendon and the acromion process.

When we stand in Mountain pose (arms relaxed), there is ample space in the subacromial space for the supraspinatus tendon and the bursa sac. When we lift our upper arm bone outwards (abduction) or towards certain angles of significant forward movement (flexion), the humerus closes into the subacromial space. For some people, due to bone structure and reduced subacromial space, they are more prone to having the tendon and/or bursa sac being compressed and stressed (aka shoulder impingement). With frequent compression, the tendon and/or bursa sac may develop conditions of inflammation. As with any acute or chronic development of shoulder impingement conditions, you will want to consult a qualified health professional for proper assessment and therapeutic treatment.