Dangers of Lumbar Flexion in Yoga

Consider the number of times you flex forward at the waist or hips in a yoga class. Lower back flexion in yoga presents a number of risks when done improperly. We often hear our yoga teacher telling us to hinge at the hips instead of the lower back. Let’s consider what these cues really mean and offer in creating a safe forward bending yoga posture. First of all we have to go through a bit of yoga anatomy and biomechanics to understand the issues involved in this common movement.

Our spine is composed of twenty-four mobile vertebrae. The cervical spine includes the top seven vertebrae, while the thoracic spine is made up of the middle twelve, and the lumbar spine completes the count with the bottom five. Below the last lumbar vertebrae are the sacrum and coccyx. The sacrum is a triangular shaped bone that is actually the fused remnant of five sacral segments. The coccyx, also known as our “tailbone,” is an even smaller triangular bone that sits below the sacrum.

Both our cervical and lumbar spines take on a curve that is known as a lordosis. This lordosis essentially means that the cervical and lumbar curves’ concave sides face the front of the body; while our thoracic curve’s concave side faces the back of our body.

In-between each vertebra is an intervertebral disc. The basic functions of the discs are to act as vertebral shock absorbers and as spacers for the spinal nerves to exit the bony vertebral column. Our spinal cord runs down the inside of our vertebrae; each spinal nerve that divides from the spinal cord supplies a particular part of the body with neurological function. This explains many of the symptoms people get when they herniate or bulge a disc (burning, aching, pins and needles, tingling, pain, and weakness through particular parts of the limbs).

Intervertebral discs are round in shape with thick outer borders and jelly-like contents within the border. Each time we bend forward at the low back, the back side (posterior side) of the disc weakens. Over time, with excessive lumbar spinal loading or flexion, the disc develops microtears. Sometimes, these microtears can produce symptoms that are relatively mild; however, when the tears become more significant, symptoms become quite severe. If the thick border has enough microtears or one large tear, the inner jelly-like substance can squish out of the tear to either chemically irritate or physically compress the spinal nerves that exit the spine off of the spinal cord.

How is this complicated anatomy relevant to yoga, picking up a piece of paper off the ground, or even bending over to brush your teeth? Lumbar flexion is the movement of bending forward at the low back while rounding the spine. Due to the lordosis (lumbar curve), this position of flexion increases the likelihood of intervertebral disc microtears which then increases the chances of disc irritation, bulging, and most severely, herniation. A disc injury is one you most definitely want to avoid as they are hard to recover from and they increase your chances of low back injury recurrence; never mind the fact that they cause a lot of pain and can cause symptoms severe enough to require surgery due to neurological complications.

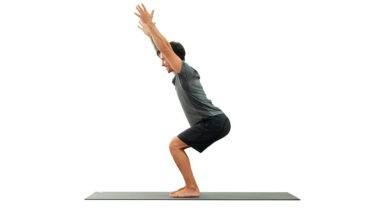

You must now be wondering how to keep your back safe while bending forward either on your mat or in your activities of daily living. When you bend forward, think about keeping your buttocks out and maintaining the natural curve in your lumbar spine. When you are standing straight up and when you bend forward, your lumbar curve should not change shape (much). Hinge forward at your hip joints instead of at your lumbar spine. People always say, “I bend my knees when I flex forward so I am ok!” My answer to that is that you can flex your knees all you want, but if you flex your lumbar spine as well, your back is at risk of injury. If you have to pick something up off the ground, the best way to do it is to both flex your knees AND keep you buttocks out to maintain your lumbar curve.

These principles apply to yoga as we bend forward quite a bit while on our mats. The repetitive action of improper forward flexion is dangerous, so be aware of your lordosis while you flex forward in poses while on your feet, on your back, or on your buttocks. This is even something you should think about while sitting at work; if you slouch through your lumbar spine, you are loading the discs which in time leads to microtears.

Understand your lumbar lordosis as it is your power position in everything you do. Take care of your back by being aware of how you flex forward and never compromise your back to reach further on your yoga mat.

Explore the Anatomy and Correct Alignment of Headstand Pose

Knowledge dissolves fear. With a basic understanding of the structures in your neck, and application of these five keys, one can practice sirsasana safely.

Let’s first take a look at the anatomy, and the neck’s role in our daily life.

The seven little bones of the cervical spine (neck bones) are unique in that they are designed for mobility rather than stability. Like other joints in the body, where stability is sacrificed for mobility, the primary purpose of the C spine in daily life is ease of movement. Therefore, ideal alignment and muscular harmony are particularly important.

The load bearing structures of a cervical vertebrae are the body and two articular facets. A typical cervical vertebral body is approximately two centimeters in diameter depending on the vertebrae (C3 – C7), gender, and individual differences. This is comparable to the diameter of a dime. One may make the comparison of a lumbar vertebral body and cervical vertebral body to the chunky heel of a walking shoe to a high heeled pump. Imagine walking a gravel road in stilettos versus the former.

Another feature worth noting is that the C spine houses the vertebral arteries. Transverse foramen, or holes from top to bottom on the side wings of the bones, house this paired blood vessel which travels up to the brain, taking a rather alarming posterior jog at the top of the neck bones before entering the skull. Symptoms of blocking this small artery include dizziness, blurred vision and occipital headaches. Any lesion compromising the integrity of this passage way is exacerbated by misalignment and the additional and uncustomary weight of your body on the cervical vertebrae in a posture like sirsasana.

Nerves exit the intervertebral foramen (holes in the sides between the neck bones), the branches of which pass laterally between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. These muscles help to hold your head and neck up like guide wires, and provide movement in your neck. Overuse these muscles through misalignment or overload them, and they will become inflamed or tight, possibly pinching the nerves.

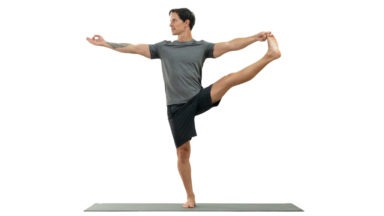

How to Safely Practice Headstand (Sirsasana)

Armed with this information, how can you incorporate sirsasana safely into your practice? Headstand or any posture for that matter doesn’t have to look like the pose in your yoga syllabus to start. Practice the actions of the pose in a modification, and you will receive more benefit than forcing the pose.

Here are some important points to practice sirsasana.

1. A strong headstand begins with sensible upright posture.

Carry your upper palate above your physical heart. Assume a natural lordosis in your neck. Your best posture will be your tallest, most easeful posture. Maintain this easeful alignment of your spine in upright yoga postures. If you don’t know what good alignment feels like upright, you won’t know what it feels like upside down.

Practice holding Tadasana in ideal alignment and full attention for several minutes. To simulate the postural muscles further, root down from the outer hips into your feet. Place a block on top of your head while standing, and root up into it from your upper palate as you gently resist. Breathe fully to expand and lengthen your torso. Drop your shoulders away from your ears, and slide the upper arms back to widen the clavicles (collar bones). Invite the ribs back, as this action tends to cause them to splay forward. Breathe into your back, particularly just above the waist.

Practice integrating your body from head to feet with these polar actions of rooting and lifting. When you are in perfect alignment, your body will feel like your favorite pair of walking shoes: No friction, no effort, just ease.

Which brings me to the next key.

2. Stretch your hamstrings and plantar fascia.

To get into any posture, the closer to ideal postural alignment you can get, the less likelihood of injury. To keep your neck safe in headstand, you need to be able to align your entire spine before taking away the support of your feet. In order to achieve this, the back of your legs and soles of your feet must be supple enough to walk into the posture without rounding the lower back and therefore the neck.

3. Apply the rules of progressive overload.

No one walks into a gym and does a clean and jerk with 150 pounds off the bat with no experience. So why would headstand be any different? The neck is accustomed to bearing a mere ten pounds of weight. Add resistance incrementally in weight and duration.

4. Create a stable foundation.

** **When you are ready to do sirsasana, interlace your fingers into prayer hands, with the exception of your pinky fingers. Your pinky fingers should be stacked, overlapping each other front to back. You should be able to see both middle fingers from above but not any of your palm to start–so slightly pronate your forearms. Once you tuck your head into your palms, the tendency is to roll onto the dorsum (back) of your hand. Starting in slight pronation will bring you into neutral alignment once you are in the posture. Now root down through parallel upper arms into the forearms, wrists and hands while keeping the spine neutral and your chest open. Nestle the back of your head into your hands. Distribute the weight between the crown of your head, forearms, wrists and hands.

5. Keep your mouth shut.

This one is mostly for teachers. Although designed primarily to aid in tongue movement and swallowing, the variety of muscles attached to the base of the tongue help to support your neck. Anchor the tongue to the roof of your mouth for additional stability. When it comes to standing on your head, recruit as much help as possible. So teachers, explain your demo first, and don’t speak once you are in the posture.

Precautions and Contraindications

There are precautions and contraindications to performing sirsasana, such as osteoarthritis of the C spine, any autoimmune disease affecting the musculoskeletal system, diabetes, heart condition, degenerated discs, down syndrome, or any other pathology affecting the neck.

However, even with these conditions, one can enjoy many of the benefits of the pose by simply embodying the actions of the pose in a modified form. With patience and keen attention, headstand can be performed safely to benefit your wellbeing.

Naomi Friesen possesses a deep understanding of the physical body through 20 years of teaching movement and anatomy. Students benefit from her knowledge of sound biomechanics by receiving safe and effective instruction. A personal trainer, pilates instructor and lifestyle/weight management coach for 12 years, she now teaches yoga after receiving her yoga instructor certification through Open Source Yoga School. Naomi’s intention is to facilitate connection for herself and students through yoga – connection to Source, connection between the parts of our body, our connection to others.

Website: www.victoriaschoolofyoga.com

Facebook: Victoria School of Yoga