New Study of Cave Paintings Say Ancient Man Understood Astronomy

A reinterpretation of one of the world’s most famous primitive cave paintings seems to show our ancient ancestors had a much stronger grasp on astronomy than we’ve given them credit. According to a recent study, cave paintings in France depict animals that represent the constellations, showing the artists who drew them were aware of the precession of the equinoxes — a discovery not thought to have been made before Hipparchus of Ancient Greece.

Of the paintings in question, researchers Martin Sweatman, Ph.D., and Alistar Coombs studied an image titled, “The Shaft,” which portrays a collapsing bird-headed man, a bison eviscerated by a spear, a horse, and a rhinoceros in the Lascaux caves of southern France’s Dordogne region.

In the past, this scene was interpreted as a shamanic ceremony or the scene of a hunt, however the exact meaning has been widely disputed as depictions of men were incredibly uncommon in this era. But according to Sweatman and Coombs’ latest study, the paintings show not only a more primordial understanding of astronomy, but also religion, science, and mathematics.

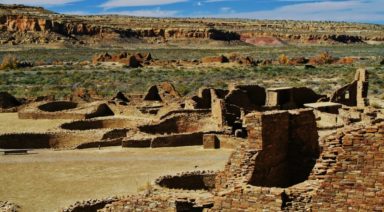

By comparing radiocarbon dating of paint samples to the position of constellations in the sky when the art was created, the researchers were able to match specific animals with correlating constellations of the solstice and equinox. They used this same method at similar archeological sites, including the ruins of Göbekli Tepe and Catalhöyük, as well as the famous cave art of Chauvet and Altamira.

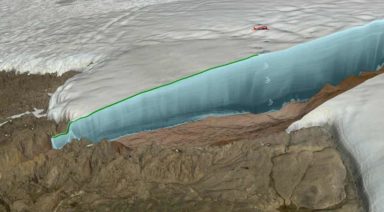

The two also said they believe the Lascaux paintings commemorate a comet striking Earth, correlating with what they believe to be the cataclysmic impact event that marked the beginning of the Younger Dryas period – evidence of which was recently found in the form of a 19-mile wide crater beneath a Greenland ice sheet.

In addition to these sites, the researchers incorporated the Lion-man figurine from the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in Germany, which dates back 38 thousand BCE and is considered to be the world’s oldest sculpture – they believe it too, may be evidence of zodiacal awareness. Their study was published in the Athens Journal of History.

Like any bold claim made of early humans which challenges long-held archeological timelines, this latest theory has unsurprisingly sparked controversy with some of Sweatman and Coombs’ colleagues who have labeled their method flawed.

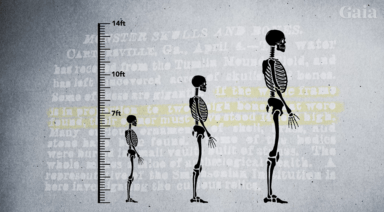

According to their model, prehistoric men from the Stone Age discovered the precession of the equinoxes some 36 thousand years before Hipparchus – a bold claim to say the least!

But findings such as this seem to continually piece together disparate pieces of a puzzle that modern archeology has glossed over or ignored entirely. And as Graham Hancock likes to say upon the discovery of new paradigms like this may be, “things just keep getting older.”

For more on the anomalous archeological finds cluing us into our forgotten past, check out this episode of Disclosure with Graham Hancock:

How the Mystery of Puma Punku Rivals the Pyramids

Pumapunku, also spelled Puma Punku, is the remains of an Incan holy site in the jungles of Bolivia that has attracted much attention as of late. The name means “door of the puma,” and as far as archaeologists know, Puma Punku was a thriving, ancient town originating somewhere around 500 and 600 C.E.

Here we are, a century and a half later, and irrepressible rumors continue to grow that Puma Punku’s massively heavy stone block structures were cut so precisely that highly advanced, ancient technology seems to be the only explanation for their incredible stone masonry.

The Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) civilization, which predated the Inca, likely influenced them through advanced stonework and agricultural practices. Although the Tiwanaku had declined before the Inca rose to power, the Inca may have adopted and adapted their techniques.

Located 45 miles west of the modern-day city of La Paz, Puma Punku is situated in the still-thriving city of Tiwanaku, high upon a desert plateau of the Andes Mountains, at an altitude of more than 12,000 feet. Tiwanaku is significant in Inca traditions, where the world was once believed to be created.

In this isolated part of the world, the ruins of Puma Punku showcase smooth stone structures made from large andesite and sandstone blocks, featuring precision cuts, clean right angles, and expertly fitted joints without the use of mortar. The megaliths are among the largest on earth, with some weighing several tons. While many of the structures are still standing centuries after their inhabitants disappeared, most of the buildings are scattered and broken around the area, leaving researchers to wonder what possibly could have moved around impossibly heavy buildings.