The CIA’s Attempt at Feline Espionage: Operation Acoustic Kitty

In the past we’ve written about some pretty bizarre and horrifying tactics the CIA tested in order to spy on the Soviets during the Cold War, but this one takes the cake by far. During the 1960s, someone at Langley had the brilliant idea to implant recording devices and antennas in cats, with the intention of training them to slip into the Soviet embassy and covertly record conversations. They gave this strange idea the not-so-subtle codename, Operation Acoustic Kitty.

If this program sounds absurd that’s because it was, and it ended in an even more ridiculous manner, after millions of dollars – and we mean millions – were invested in R&D. Those in charge of the program hoped to utilize the inquisitive nature of the feline species, but in the end, it was in fact curiosity that killed the cat — or maybe just sheer terror.

Spy Cat

The exact details surrounding Operation Acoustic Kitty have been debated by members of the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology, but according to its then-director Robert Wallace, the program originally experimented on other animals, such as rats and ravens, using a tactic called passive concealment. There is even a YouTube video of Wallace casually discussing the use of dead rats as covert recording devices, while waving around a taxidermized rodent in front of an audience.

When the program shifted its focus to felines, it needed to figure out the most appropriate way to wire a kitty. There is, after all, more than one way to skin a cat…

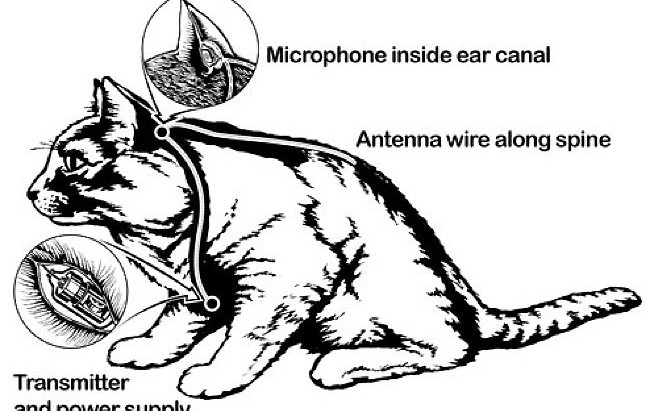

After incising and implanting a power pack in the cat’s abdomen, a cord was run along the length of its spine, connecting wires to a recording device in the cochlea of its ear.

They then sent the cat on a training mission and supposedly had some brief successes. That was until the cat got hungry or… aroused. So, the agents decided to implant more wires to suppress the cat’s urges and keep it focused on the target at hand, creating a true cyborg kitty.

Once the poor tabby was electronically rigged, it was loaded into an unmarked van with surveillance equipment and driven across town. They let the cat out of the bag across the street from the target embassy hoping it would find its way inside.

The cat bolted across the street, making it no more than 10 feet before it was flattened by a city taxi. The CIA’s $20 million investment – which equates to nearly $160 million adjusted for inflation today – was destroyed in a matter of moments.

But according to Wallace, this embarrassing failure was not the reason the program was discontinued. Instead, he and his team realized the famous aphorism was true… what they were trying to do was impossible, it was like herding cats. Actually, that’s literally what it was.

The CIA documents state:

“Our final examination of trained cats convinced us that the program would not lend itself in a practical sense to our highly specialized needs.”

It goes on to conclude that cats can be trained, but due to environmental and security factors, using the technique in a real foreign situation was not practical. Essentially, they decided to develop a more concrete plan – it was time to stop pussyfooting around.

Another Failed CIA Project

So, who’s brilliant idea was it to use the most notoriously intractable domestic animal to spy on Soviet adversaries? That’s hard to say. But supposedly the impetus came from the fact that the target area was rife with feral cats. Agents assumed their feline spook could blend in with all of the strays, evading detection by the embassy’s security, or worse, cat fights.

And when it came to admitting to the project’s utter failure, it seems the cat had the CIA’s tongue until the early aughts when a FOIA request exposed many of the CIA’s Cold War espionage programs. Then in 2001, Jeffrey Richelson, an executive assistant to the CIA Director in the ‘60s published a book titled The Wizards of Langley, in which he discussed the embarrassing letdowns of Operation Acoustic Kitty.

“A lot of money was spent. They slit the cat open, put batteries in him, wired him up. The tail was used as an antenna. They made a monstrosity,” he said.

Richelson also says he believes that even if the cat wasn’t instantly squashed by an oncoming taxi, the poor animal would have soon perished from the crude surgical implants. PETA would not have been pleased.

And while Project Acoustic Kitty wasn’t nearly as nefarious as MKUltra, Project Artichoke, and others, it was an insanely expensive waste of taxpayer dollars that would certainly cause an uproar today.

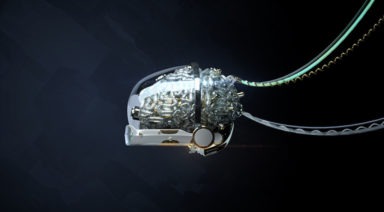

But that doesn’t mean it’s not still happening. DARPA has been working on similar projects involving robotic insects able to fly, swim, and crawl into small crevices and other generally inaccessible areas. Ostensibly, these insectoids will be used for disaster recovery, though if Acoustic Kitty has set any precedent, it would be a surprise if espionage wasn’t on the table.

Because when it comes to spying on allies and adversaries alike, the U.S. surveillance apparatus certainly considers itself to be the cat’s pajamas.

Sorry, no more cat puns.

How the Soviets Weaponized EMFs During the Cold War

During the Cold War, American state department employees dreaded assignments to Moscow, known as “the sickest embassy in the world.” From the 1950s to 1979, Russians blasted the U.S. Embassy with non-ionizing microwave radiation (2.5 to 4.0 GHz), some say for 40 hours a week. According to a well-known study, “Although the [microwave radiation] intensity reaching the embassy was approximately 500 times less than the U.S. standard for occupational exposure, it was twice the highest limit allowed by the Soviet standard.” 2.5 to 4 GHz are part of the range (up to 10 GHz) that includes modern wireless networks and cell towers, radar, 4 and 5G, smart meters, and cell and cordless phones.

Dr. Paul Dart MD, a researcher studying the health effects of smart meters, noted that “The US embassy personnel had a statistically significant increase in depression, irritability, concentration problems, memory loss, ear, skin, and vascular problems, and other health problems. The longer they worked there, the worse these problems were likely to be.”