Victims of CIA’s MKUltra Mind Control Program Fight Back

The Netflix series, Wormwood, reignited mainstream attention on the horrors of MKUltra– the government-funded mind control program of the 1950s and ‘60s that used experimental brainwashing techniques on unwitting citizens. And now a number of families are coalescing to bring a class action lawsuit against the agencies involved to gain reparations and a modicum of closure for the horrific experiments endured by their loved ones.

In the late ‘50s, a man named Dr. Ewen Cameron headed the Allen Memorial Institute at McGill University in Montreal. Cameron was a renowned psychiatrist, who became notorious for his role in driving a number of people to the brink of insanity with experiments intended to break down or “de-pattern” his subject’s thoughts.

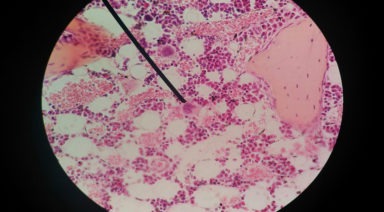

Cameron’s methods essentially amounted to psychic torture; injecting patients with mega-doses of LSD, inducing sleep for weeks at a time, using electroshock treatment, and relentless exposure to taped recordings – some played up to half a million times.

Most of Cameron’s patients had admitted themselves to the hospital for relatively minor conditions such as postpartum depression or anxiety, not knowing they would become guinea pigs for such an insidious experiment.

Once they were released back into society most were unable to cope, their psyches having been completely shattererd. For those who were able to re-assimilate, life was incredibly difficult – some were able to suppress the trauma, though others remained severely disturbed for the rest of their lives. One woman would explode in a fit of rage if a stranger bumped into her. Another said she was psychologically and emotionally reduced to the state of a toddler.

In 2017, one particular victim’s daughter, Alison Steel, was quietly awarded a sum of money from the Canadian government for her mother’s unknowing participation. Jean Steel was admitted into the Allen Institute program in 1957 for manic depression, before quietly being ushered into one of Cameron’s tests. Upon release from the clinic, she was never the same.

Steel’s daughter was given $100,000 from the Canadian government after signing a non-disclosure agreement, but now, a number of victims have come forward asking for reparations.

In 1992, the Canadian government set out to provide restitution the families of 77 victims involved in the program, though many were never compensated because they were not considered to have been damaged enough.

A class-action lawsuit was brought against the CIA in the 1980s, with nine families asking for a $1 million settlement, though the government paid just $80,000 each.

Now, a group of families in Quebec are seeking reparations from the Canadian government, provincial government, and possibly McGill University for damages and a public apology. Some members involved in the suit say that some acknowledgement of wrongdoing by the government would mean more than a hushed settlement.

Weather Modification Technology -- Decades of Ever-Increasing Tempo

Weather Modification Technology – Good Idea or Bad? The Science of Playing God and an Overview of the Technologies

To what extent people are able to control the weather is a bit of a mystery to most. It has been a goal for ages, and perhaps could even be considered the “final frontier” in dominating and controlling Mother Nature. Despite fairly familiar terms such as “cloud seeding,” most believe that controlling the weather on a large scale cannot be done. Control a hurricane? Nonsense! Besides, the idea of controlling the weather with weather modification technology or weather changing machines is a bit alarming to most people. The sheer arrogance of such a proposal has the flavor of “playing God.”

Indeed, even at our technologically advanced state, the inner and outer workings of our planet still hold many mysteries. Have humans really advanced enough to actively manipulate this balance without harming or disrupting the overall planet? Of course, this harmony has been disrupted by climate change, the causes of which continue to spark heated debate. Regardless, with the growing concern over our changing climate, is it possible that weather modification technology could help?