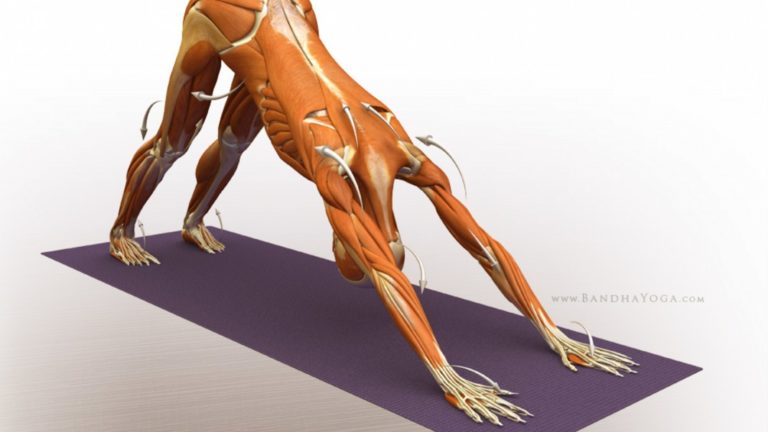

Adho Mukha Svanasana: Downward Facing Dog Pose Exploration

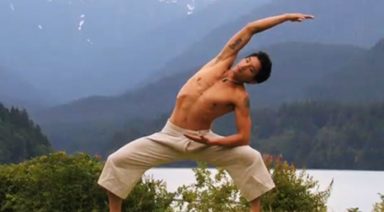

Adho Mukha Svanasana is both an inversion and an arm balance. It is the resting point in the Vinyasa sequence and serves as a barometer for the stretch at the backs of the legs as well as the shoulders. Flexing the hips and straightening the knees focuses the stretch on the hamstrings. You can dorsiflex the feet to emphasize the stretch of the gastrocnemius (which crosses the backs of the knees) and soleus (which crosses the ankles with the gastrocnemius). Straightening the arms to press the body back toward the legs indirectly deepens the stretch.

Address these basic movements first. From there you can focus on the nuances of Dog Pose, remembering that many of the most profound experiences of yoga take place with small, concentrated, and subtle movements. For example, pronating the forearms while externally rotating the shoulders creates a “coiling” helical effect up and down the lengths of the arms; this tightens the elbow ligaments and stabilizes the pose. Another subplot in the story involves opening the wings of the iliac bones to allow the sacrum to tilt forward. Do this by attempting to “scrub” the feet outward on the mat. This engages the abductor muscles in a closed chain fashion, moving their origins on the iliac crest. Engage the buttocks by attempting to scrub the feet away from the hands. Pronate the ankles by pressing the weight into the balls of the feet. Then lift the arches to spread the weight to the outer edges. This balance of eversion and inversion at the ankles stabilizes the pose from its foundation. You can use any or all of these nuances as you walk through and deepen the asana.

BASIC JOINT POSITIONS

- The hips flex.

- The knees extend.

- The shoulders flex and externally rotate.

- The elbows extend.

- The forearms pronate.

- The wrists extend.

- The ankles dorsiflex.

- The lumbar spine extends.

- The cervical spine flexes.

Preparation

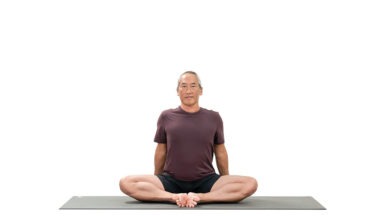

Adho Mukha Svanasana is practiced as a free-standing posture or as part of a Vinyasa sequence. If you’re using it in Vinyasa, then for the first few rounds, simply take the basic shape of the pose by flexing the hips and straightening the knees and elbows. This prepares the major muscle groups that are stretching. Once you are warmed up, begin adding synergist muscles to refine the pose, as described in the steps that follow. For the free-standing version, begin on all four. Get a feel for pressing the palms into the mat. Spread the fingers evenly apart and rotate the shoulders outward. Turn the toes under to place the weight onto the mounds of the feet. Lift the knees and flex the trunk towards the thighs. Activate the triceps to straighten the arms. Then, keeping the trunk flexed, straighten the knees to come up into the pose. Ease out of Downward Facing Dog by bending the knees and coming back to the floor. Rest in Child’s Pose. You can use the chair stretch illustrated below to lengthen the shoulder extensor muscles. Turn this into a facilitated stretch by pressing the elbows onto the seat of the chair for several breaths. Then take up the slack produced by the relaxation response.

S T E P 1

Flex the hips by contracting the psoas muscle and its synergists, including the adductors longus and brevis and the pectineus. A cue for engaging these muscles is to attempt to drag the feet towards one another. Bend the knees at first. This releases the pull of the hamstrings on the ischial tuberosities and allows the pelvis to tilt forward when the psoas contracts. Note the origin of the psoas major on the lumbar spine. Engaging this muscle also draws the lumbar spine forward, slightly arching the lower back. This is a desired form for Dog Pose. Activating the psoas produces reciprocal inhibition of the gluteus maximus (a hip extensor).

S T E P 2

Several muscles synergize the actions of the psoas. The pectineus and adductors longus and brevis flex the hips and tilt the pelvis forward. The sartorius and rectus femoris also flex the hips, since they cross the joint on their way to the knee. Note the origins of these muscles on the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS). Activating them draws the pelvis forward. A cue for contracting the rectus femoris is to lift the kneecap (where the muscle inserts). The sartorius is more difficult to isolate, but it will engage when you flex the hip, especially if you externally rotate the femur. The gluteus minimus crosses the hip on the outside of the ilium. Its action varies depending on whether the hip is flexing, neutral, or extending. The hips flex in Dog Pose, at which time the gluteus minimus also acts as a flexor. The gluteus minimus is a small muscle that lies deep to the other gluteals, making it difficult to contract at will; use visualization to engage it.

S T E P 3

Activate the triceps to extend the elbows. Pronate the forearms (with the pronator teres and quadratus muscles) to press the mounds of the index fingers into the mat. Contract the anterior deltoids to draw the shoulders forward. The cue for this is to imagine lifting the arms overhead. Balance pronation of the forearms with a supination force by engaging the abductor pollicis and extensor pollicis longus to lift the thumbs and draw them away from the palms. Gently contract the biceps as well to contribute to this action.

S T E P 4

Engage the quadriceps to extend the knees. Activate the gluteus medius and tensor fascia lata to draw the iliac bones slightly apart (through closed chain contraction) and internally rotate the thighs. A cue for this is to fix the feet on the mat and then attempt to scrub them away from each other. Because the feet won’t move, the force of this contraction is transmuted to internal rotation, creating a “coiling” line of force down the legs.

S T E P 5

Contract the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles to externally rotate the shoulders. The posterior deltoids contribute to this action. Draw the shoulders away from the neck with the lower third of the trapezius. Note how this opens the chest.

S T E P 6

Engage the tibialis anterior to lift the tops of the feet toward the shins. This draws the heels toward the mat, stretching the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles of the calves and the flexor muscles of the toes. Then contract the peroneus longus and brevis muscles on the sides of the lower legs to evert the ankles, pressing the balls of the feet into the floor. Finally, stabilize the ankles by slightly inverting them to lift the arches and spread the weight to the outsides of the feet.

SUMMARY

Dog Pose stretches the muscles at the backs of the legs and the superficial back muscles. These include the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and posterior deltoids, as well as the gastrocnemius/soleus complex, long toe flexors, hamstrings, and gluteus maximus.

Disclaimer

Always, in your particular case, consult your health care provider and obtain full medical clearance before practicing yoga or any other exercise program. Yoga must always be practiced under the direct supervision of a qualified instructor. Practicing under the direct supervision and guidance of a qualified instructor may reduce the risk of injuries. Not all yoga poses are suitable for all persons. Practicing under the direct supervision and guidance of a qualified instructor, in addition to the direction of your health care provider, can also help determine what poses are suitable for your particular case. The information provided in the blog, website, books, and other materials is strictly for reference only and is not in any manner a substitute for medical advice or direct guidance of a qualified yoga instructor. The author, illustrators, editors, publishers, and distributors assume no responsibility or liability for any injuries or losses that may result from practicing yoga or any other exercise program. The author, editors, illustrators, publishers, and distributors all make no representations or warranties with regards to the completeness or accuracy of information on this website, any linked websites, books, DVDs, or other products represented herein.

Legs-up-the-Wall | Yoga Pose

ADJUSTMENTS | BENEFITS | CONTRAINDICATIONS | MANTRA | MUDRA | PREP POSES | SANSKRIT | STEPS | TIPS

Viparita karani (vip-par-EE-tah car-AHN-ee), or legs-up-the-wall pose, is a restorative inversion that can ease the mind and relieve painful symptoms such as tension and cramps. Many people enjoy this pose using props — you may want to have a pillow, bolster, or folded blanket nearby.