The City of Eridu is the Oldest on Earth, It’s Largely Unexplored

Over the past decade, there have been a number of archeological revelations pushing back the timeline of human evolution and our ancient ancestors’ various diasporas. Initially, these discoveries elicit some resistance as archeologists bemoan the daunting prospect of rewriting the history books, though once enough evidence is presented to established institutions, a new chronology becomes accepted.

But this really only pertains to the era of human development that predates civilization — the epochs of our past in which we were merely hunter-gatherers and nomads roaming the savannahs. Try challenging the consensus timeline of human civilization and it’s likely you’ll be met with derision and rigidity.

Conversely, someone of an alternative persuasion may profess stories of ancient civilizations, such as Atlantis or Lemuria, with speculative mythology recounting a lost, golden age in human history that was surely responsible for building the pyramids and other wonders of the world. They point to the writings of Solon and Plato as evidence for these ancestors’ existence, which is exciting but difficult to corroborate without physical proof.

Researcher Matt LaCroix seems to find himself somewhere in the middle of these two perspectives. While he says he’s fascinated by the Athenian clues detailing the destruction of Atlantis, he finds more compelling evidence in ancient Mesopotamia, or what academia already acknowledges as “the cradle of civilization.”

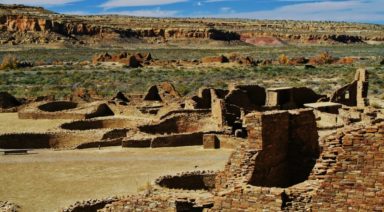

It’s here we find the ruins of the most ancient city on Earth that we have physical proof of — the city of Eridu. This archaic metropolis is well-documented in historical texts covering ancient Sumer and the Babylonian empire, but there’s also a mythological component to Eridu that may imply human civilization is far older than we believe — significant orders of magnitude older.

That mythological component comes from the Sumerian King List; a record of ancient monarchs and demi-gods dating back more than 250,000 years to the time when “kingship first descended from heaven.”

This royal chronicle ostensibly reads like mythology, with early kings said to have lived and ruled for tens of thousands of years, particularly during the antediluvian era. After the flood, however, the kings’ reigns begin to shorten to hundreds of years — much like some of the patriarchs of the Old Testament — and eventually to lifespans matching our modern mortality. Not to mention, there’s proof that the names of some of the more contemporary kings on the list did, in fact, exist.

The attempts to preserve documentation of this wildly ancient lineage trace back to the last great Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, who ruled several thousand years ago. Thanks to his efforts compiling a massive library of Sumerian culture that was already ancient in his day, we have texts including the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Enūma Eliš that survived into modernity. Millennia later, these texts outlining the Sumerian pantheon would be discovered and translated by Austen Henry Layard, before then being famously interpreted by Zecharia Sitchin.

Sitchin’s translations inspired many to ascribe to the idea that the Anunnaki gods of Sumerian lore were an extraterrestrial race of humanity’s progenitors. LaCroix says Sitchin’s perspective intrigued him at first too, but as he dug deeper he found details the alternative scholar got wrong. Namely, the idea that humans were created as a slave species for an industrious race of alien overseers who used humans to mine precious earth minerals.

Instead, LaCroix says the texts describe an incredible effort by a subset of the Anunnaki known as the Igigi, to build infrastructure on Earth that would allow civilization to flourish before creating mankind as a perfect species with the potential to ascend to enormous power — maybe even more than the Anunnaki themselves.

According to LaCroix, there may have been a number of times we came close to reaching that potential throughout our history on this planet, but we’ve been set back by natural disasters and conflict. These setbacks have sadly continued over the past decade as the war in the Middle East has led to the destruction of precious artifacts that could give us more insight into, arguably, the most important period in human history. These artifacts, particularly the countless cuneiform tablets in places like Nineveh, have been looted and sold on black markets around the world.

And if these sites are not being destroyed by religious extremists, they’re being largely ignored by archeologists. A prime example of this is Eridu and its iconic ziggurat, the temple of E-Abzu, which remains buried in the sands of southern Iraq. According to Sumerian legend, Eridu was established by, and home to the Annunaki god Enki, himself. Here, cuneiform tablets are literally sticking up out of the sand waiting for the right people to come along, preserve them, and unlock the lost secrets of humanity.

To learn more about LaCroix’s work to help preserve these records watch Eridu: City of Gods on Open Minds with Regina Meredith.

Evidence the Knights Templar Migrated to Brazil

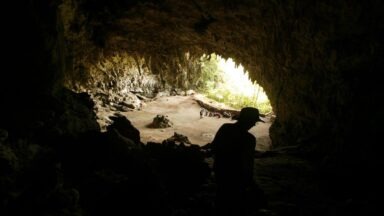

In the heart of Brazil lies a cave with carvings that may rewrite history. Long before Columbus set foot in the New World, a Medieval society had already taken root. Now researchers are looking for what drove this group across the Atlantic Ocean.

What were they in search of, and what secrets do they now offer the world? A new documentary titled, “The Brazilian Templars Mystery,” sheds light on one of the most overlooked clues to our past and one of the most intriguing and misunderstood cult of warriors — the Knights Templar.

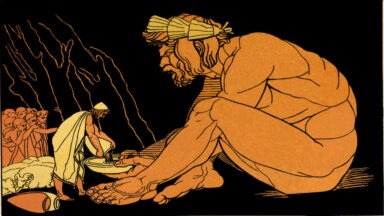

Around 1118 A.D., Hugues de Payens, a French knight, created a military order, along with eight relatives and acquaintances, who became known as the Knights Templar. The order grew rapidly into a large organization of devout Christians during the Middle Ages, charged with an important mission: to protect European travelers on their pilgrimage to the Holy Land and carry out military operations that would ensure a free flow of unhindered pilgrims.

The members of this colorful order of knights swore oaths of poverty and chastity and wore a distinctive badge bearing a red cross on a white mantle. As pilgrimages grew in intensity, so did the numbers of Templars until they became Medieval Christendom’s leading military order.

Over time, the Templars gained a reputation as a wealthy, powerful, and mysterious order that was well-known for their activities as droves of travelers made their way to the holy sites of Jerusalem. When Christian armies wrested control of Jerusalem in 1099 A.D., the Templars opened the floodgates for more and more pilgrims to join.