The Megalithic Baalbek Temple; An Ancient ‘Landing Place?’

When one considers the mysteries of ancient megalithic ruins, famous sites such as Stonehenge, Palenque, and Göbekli Tepe come to mind, though less often are the temple grounds of Baalbek mentioned in the same breath. There, perched 3,000 feet atop a sacred hill in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, lay the ruins of one of the world’s most massive megalithic sites, containing some of the heaviest quarried stones of antiquity. Still, little is understood of its construction.

Baalbek is located in the northeast of Lebanon, about 60 miles outside of Beirut, making it a difficult place to travel these days. But during the time of Roman imperialism, it was known as Heliopolis, the “City of the Sun,” founded by Alexander the Great in 334 BC. Baalbek became the site of Roman temples dedicated to Jupiter, Bacchus, and Venus, based on a popular cult devoted to this famous triumvirate.

Though the foundational stones and the location in which they were quarried have been known for some time, the site’s biggest megalith was discovered just recently. Weighing in at a whopping 1,620 tons, it outweighs another mysteriously gargantuan monolith from the same quarry, known as the Pregnant Mother Stone, by 400 tons.

The remains of the Roman temple rest on a stack of three, 900-ton megaliths known as the trilithon. Moving the trilithon into place today would require the effort of some of the world’s most powerful cranes, yet in the time of its alleged construction, the stones were somehow situated through primitive means so precisely, that one has difficulty slipping a sheet of paper between them today.

To put the sheer weight of these stones into perspective, one might compare them to the stones used to construct Stonehenge, which weighs in at around 25 tons each – a fraction of the trilithon stones’ weight.

Researchers including Graham Hancock, find this difficult to comprehend, leading him to believe in the possibility that an antediluvian, or pre-flood, civilization with advanced technology may have been responsible for the trilithon, upon which the Romans later constructed their temple. In fact, Hancock says he believes the trilithon maybe 12,000 or more years old, predating Roman construction by around 10,000 years.

The site remained a sacred place for a number of cultures and religions throughout its history and is believed, even by mainstream archeologists, to have been inhabited for the past 8-9,000 years. After the fall of the Roman Empire, it became a site of importance for Pagans, Christians, and later Muslims when the Ottoman Empire controlled the region.

The Pregnant Mother Stone at Baalbek

Baalbek Aliens

Due to the baffling size and masonry of the stonework at Baalbek, the site has sparked theories among proponents of the ancient astronaut theory due to interpretations of ancient Sumerian texts which referred to Baalbek as “the landing place.”

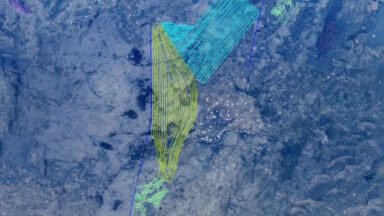

Some believe the area may be located within specific geomagnetic energy fields, where resonant electromagnetic energy was harnessed to erect the structure. Advocates of these theories, including Freddy Silva propose the possibility that Baalbek may be situated along a special energetic field due to quartz contained beneath the Earth’s surface. The quartz in the area may have worked in conjunction with the massive stones at the quarry alleged to contain piezoelectric properties, possibly aiding in the erection of the Baalbek monoliths.

Others believe it was simply constructed by an ancient civilization with advanced technology. In fact, mainstream archeology doesn’t necessarily agree that the trilithon was constructed by the Romans, but potentially some prior civilization. And if this was the case, who were these people able to move such monoliths, before the engineering brilliance of the Roman empire?

For more info on some of the world’s most confounding megaliths watch this episode of Beyond the Legend with Erich Von Däniken:

Ancient Complex at Karahan Tepe Older than Gobekli Tepe

New discoveries have been made at the ancient site of Karahan Tepe — this sister site of Göbekli Tepe may have just revealed its hidden origins and proved an ancient civilization is even older than once thought.

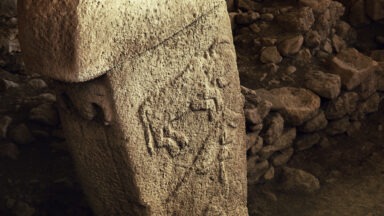

Archeologists working at the ancient site of Karahan Tepe, about 30 miles east of its sister site Göbekli Tepe, have found stunning carved heads, standing stones, buttresses, and what appear to be snakes prominently carved into the earth. The dig is being led by the University of Instanbul and in their official report point out that, not only are these and other neolithic structures the beginning of architecture but also held a symbolic purpose. Writing, “[T]hey also bear traces of the conceptual transformation of the space. It is during this period when the building was instilled to mean something other than a space to live in, whereby the construction of the first shelters was followed by that of ‘special structures.'”

Science and history writer Andrew Collins, has visited and studied Karahan Tepe since 2004 and has seen these special structures up close.

“The main structures were all what they call ‘subterranean,’ they would cut deep down into the bedrock. One was a huge elliptical stone enclosure,” Collins said. “Clearly, this was an amphitheater for ceremonial ritual activity. Yet this connected via a hole that is 70 cm in diameter into a very strange room containing 11 stone pillars, ten of which are actually carved out of the bedrock itself, and sticking out of the wall of this room that I call the Pillar Shrine, is this elongated neck with a head on the end of it — this carved stone head. This confined room is somewhere initiates or people looking for connection or communication with some kind of otherworldly force or influence or diety would come to do their attunement in altered states of consciousness.”