Yoga Anatomy: Avoid Hand and Wrist Injuries

Think of the number of times your hands and wrists are connected to the earth and carry your weight in a typical Hatha Yoga practice. Like our feet, our hands frequently become a crucial foundation from which our postures build and express themselves. Sustaining mindful engagement of our hands will support a life-long practice that is free of negative stress conditions and injuries to the wrist. Let’s look at some anatomical aspects to give us empowerment and motivation to explore our unique positioning and engagement of the hands and wrists.

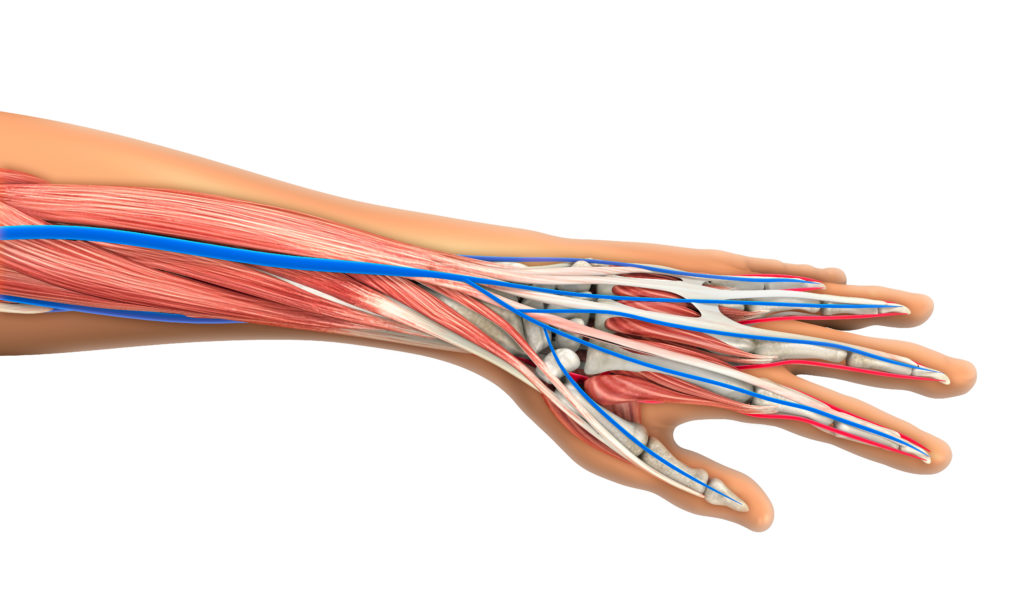

The wrists are formed by our 2 forearm bones (the radius and ulna). They meet dat the wrist joint where there is cluster of small bones (carpal bones). The carpal bones connect with 5 long bones (metacarpal bones) that make up the palm of the hand. From there, the metacarpal bones connect to the bones of the fingers (phalanges). The carpal bones form a tunnel through which tendons and nerve tissue pass to service the hand and fingers. One primary focus of hand engagement is to avoid collapsing into this tunnel and keeping excessive pressure from cascading into that track of muscle and nerve tissue.

One primary focus of hand engagement is to avoid collapsing into this tunnel and keeping excessive pressure from cascading into that track of muscle and nerve tissue.

Another key structural area to consider is the joint connection between the ulna and the carpal bones. If you turn your hand open (supination of the forearm and wrist), your ulna is the inside forearm bone (medial side). Unlike the radius (lateral or thumb side) that has a direct joint connection to the carpal bones, the ulna has indirect joint connection. Instead, there is a piece of fibrocartilage (designed to absorb stress forces) between the ulna and carpal bones along with a network of supporting ligaments – this area is called the Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex. When we look at the overall differences in joint connection, the radius also has a larger joint surface compared to the ulna. This gives indication that most people are best served to deliver a greater proportion of their force and energy through the radial side of the wrist than through the ulnar side.

How Does This Play Out in Terms of Applications?

Increase your surface area

It is common in postures like Downward Facing Dog to lift the index finger pad and have the body weight fall into the outside or ulnar side of the wrist – besides shifting force away from the radial side where the wrists are better structured to receive loads, the overall surface area of the hands decreases. When surface area decreases, pressure increases (from basic physics, Pressure = Force / Surface Area) and ultimately, this increased pressure is directly into the ulnar side of the wrist. So, by keeping a rooting sensation through the index finger and thumb pads, surface area increases, pressure decreases, and we ease that overall pressure to be carried more properly through the radial side of the wrist and not have it so heavily isolated into the ulnar side of the wrist.

Play with rooting and cupping

Hasta Bandha (“hand locks”) can come in many forms and techniques. While rooting through the index finger and thumb pads, also play with grounding motions through the middle, ring, and pinky fingers. Explore how you can creating a subtle lift through the palm of the hand – this cupping motion strengthens wrist muscular and takes pressure and collapse out of the carpal tunnel region. Note: when rooting through the index finger and thumb pads, this will create an inwards spiral of the forearm (pronation). Be mindful of the kinetic chain effect in your shoulder. As you pronate the wrist, try to lightly counter-spiral the upper arm bone (external rotation). This is will enhance shoulder stabilization and integrity. I find the ideal amount of pronation and shoulder external rotation will cause the crease of my elbow to look diagonally inwards towards my thumb. If the creases are looking at each other or directly forward towards the middle fingers, there may be too much of one spiral and not enough of the other.

Explore spreading of the hands and angles of the wrist

Find a balance of spreading the fingers (abduction) that creates a natural, inherent support for your wrists. Often, too much finger spreading creates unnecessary tension and rigidity. No one, specific alignment of the hands is perfect – we are all build differently, so play with how it best feels to align, angle and set the line of the fingers and wrists.

Changing hand width can do wonders

When the hands are close, we tend to have force loads bearing down more through the ulnar side of the wrist and into the Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex. When the hands are moved wider (and it doesn’t take much adjusting), force loads are often shifted more into the radial side. Give that try – do a small pushup movement with hands close versus wide and notice where the loading is most predominant in the wrist. From there, try slightly different hand widths in postures like Downward Facing Dog, Crow, and Upward Facing Dog .

How can hand width variability enhance these types of postures?

Remember that our bone structures are highly variable along with lifestyle patterns – some of us need to apply care and attention for the carpal tunnel, others for the ulnar side of the wrist, and even some of us have structural conditions in the radial side that require accommodation and modifications. There is never a need to practice with discomfort. Move and adjust to find your authentic lines of engagement. Also consider that Hatha Yoga is a means of applying ‘positive stress’ to our tissues to waken, strengthen, and expand them. But with any exercise program, a prudent approach to progressive, holistic overload of tissues (whether it be strengthening or stretching) is the incorporation of rest. Mix up your sequencing and styles of practices so that you can provide periods of rest for your hands and wrists. Mindfulness and nurturing go a long way in supporting a vibrant practice.

Consider that Hatha Yoga is a means of applying ‘positive stress’ to our tissues to waken, strengthen, and expand them.

Yoga Anatomy: Reducing Shoulder Impingement

![]()

![]()

Our wonderful shoulders are the most mobile joints in the body and, for anyone who has done any amount of Hatha Yoga flow, we can appreciate how much the shoulders are engaged and challenged in our practices. Given how frequently we load and stress the shoulders in yoga, it is ideal to move the shoulders with intelligence, mindfulness, and attentive care. One aspect of mindful movement and engagement is reducing the onset of shoulder impingement.

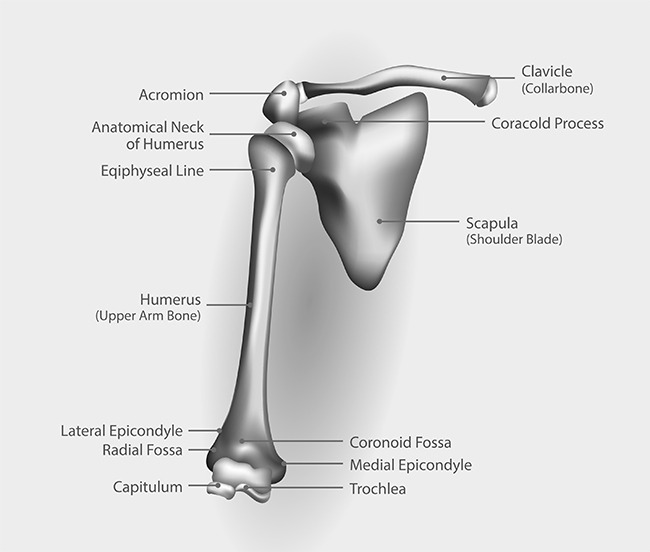

Our shoulder joints are made from a ‘ball and socket’ design. The upper arm bone (humerus) has defined structures at its proximal end (closest point to the center of the body). At the proximal end of the shaft, we see that the humerus has boney processes (called tubercles where tendons attach). Moving towards the shoulder joint, the humerus has a neck that transitions into a ‘head’ or the ball portion of the joint. The humeral head inserts into the socket (glenoid fossa or cavity) forming this highly moveable joint. The socket is part of the shoulder blade (scapula bone). There is another part of the shoulder blade with a boney projection called the acromion process which is positioned above the humerus. You call feel the acromion process on yourself by taking one hand over and to the back of the shoulder blade. Run your fingers along the shoulder blade to find a horizontal line of bone – this the spine of the scapula. Run your fingers all the way to the end into your shoulder – where this ends is your acromion process.

Between the acromion process and the tubercle region of the humerus is the ‘subacromial space.’ This is where our attention goes regarding shoulder impingement considerations. Deep above the spine of the scapula runs one of your rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus muscle), which has its tendon traveling through the subacromial space and attaching onto the greater tubercle of the humerus. To offer some protection to this tendon, there is a small sac of fluid (bursa sac) between the tendon and the acromion process.

When we stand in Mountain pose (arms relaxed), there is ample space in the subacromial space for the supraspinatus tendon and the bursa sac. When we lift our upper arm bone outwards (abduction) or towards certain angles of significant forward movement (flexion), the humerus closes into the subacromial space. For some people, due to bone structure and reduced subacromial space, they are more prone to having the tendon and/or bursa sac being compressed and stressed (aka shoulder impingement). With frequent compression, the tendon and/or bursa sac may develop conditions of inflammation. As with any acute or chronic development of shoulder impingement conditions, you will want to consult a qualified health professional for proper assessment and therapeutic treatment.