Neuroscience in Advertising; When Does it Become Mind Control?

By now you’re probably used to how predictive advertising has become, but it probably felt intrusive at first. Advertisers have always used subtle tactics to convince you to buy things, but now the privacy boundary is increasingly blurred. While it’s somewhat known that advertising finds its roots in propaganda, are developments in technology and neuroscience changing the fundamental nature of marketing into something that borders on mind control or manipulation?

The foundational elements of public relations and advertising were developed by a man named Edward L. Bernays, who happened to be the nephew of none other than Sigmund Freud. Freud gave a copy of his General Introductory Lectures, his seminal work on psychoanalysis, to Bernays as a gift in the nascent phase of his career.

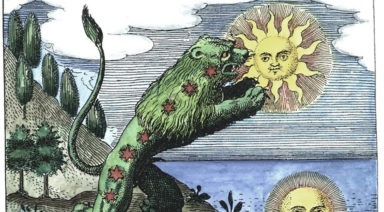

Bernays was intrigued by Freud’s research, notably the idea that irrational forces drive human behavior. He took the idea and parlayed it into what he referred to as “engineering consent,” a concept that instead of bowing to consumer demands, cultivated them.

Bernays was first hired for a Lucky Strike campaign in which he created social trends to convince more people, particularly women, to smoke. He realized cigarettes exemplified male power, so he staged a campaign to empower women to smoke cigarettes by inviting a group of young female Vogue employees to light up on New York’s 5th avenue in a show of protest.

He referred to the campaign and the cigarettes involved as “Torches of Freedom.” Later, when the ladies expressed distaste for the green color of the packaging, he staged a number of events to make the color green fashionable.

This type of consent engineering was manipulative. And there’s evidence that Bernays likely knew of the dangers of smoking in those days as he would destroy his wife’s cigarettes whenever he found them at home. Despite this knowledge, and later becoming a public opponent of tobacco, he pitched Lucky Strikes as having a slimming effect and claimed they were soothing on the throat. He even wrote a book on his tactics blatantly titled, Propaganda, that would later inspire the Nazis.

Bernays used fear tactics, false or deceptive advertising, and what can only be referred to as social mind control tactics to sell products, even if they were dangerous or disingenuous.

This set the framework for the modern tactics that continue to perpetuate this trend, and while false or misleading advertising is pretty well-regulated by the FTC, the idea of engineering consent still persists. So is it possible consent may be engineered against our own will?

Mind Control Techniques Through Neuroscience

Today, neuroscientists are at the forefront of developing incredibly exciting technology, with the potential to correct for certain cognitive disorders and diseases. Some are undertaking the daunting task of mapping out the brain and its endless neural pathways, while others focus on the more incremental steps that may one day lead there, such as interfaces for telepathically controlling our mobile devices.

Often, this technology parallels the development of artificial intelligence, with programmers attempting to reverse engineer the brain or mirror the layout of neural networks in computer systems. This type of network control is being compared laterally to brain function, with the idea that if you inject energy into one part of a digital network, it should influence another.

Scientists applied this with a technique called deep brain stimulation, or DBS, used to treat those suffering from Parkinson’s and obsessive compulsive disorder. They found unusual activity in the fronto-striatal circuit to be responsible for obsessive-compulsive disorder, which can be normalized with DBS. However, this type of energy injection can cascade across the brain, causing unintended effects.

Technology’s Creeping Mind Control

Mind control could be defined in a few ways, but the common conception requires the alteration of a person’s behavior in an observable manner, without that person’s permission. And typically, that lack of consent is known or desired by the one administering a mind-controlling function.

Not too long ago, researchers conducted a study measuring the effects electromagnetic radiation emitted from cell phones had on the brain. The study was predicated on the question of whether or not it was possible to control somebody’s mind with a cell phone.

Now, the definition of mind control, in this case, wasn’t as nefarious as the image that comes to mind when we think of dystopian sci-fi movies or Manchurian candidates but was instead much simpler. Can electromagnetic radiation from cell phones have an effect on mental behavior when transmitted at the proper frequency?

Their result turned out to be affirmative. The cell phone radiation stimulated alpha waves in the brain, particularly in areas closest to where the phone was being held. These types of waves are produced when we sleep, in wakeful states where we’re daydreaming, or when switching from external thinking to internal thinking. It’s even more unsettling when you find out that the study was conducted using, a now very obsolete, Nokia 6110.

Today, advertising is eerily predictive in our online browsing, but the majority of it is simply based on your search history. If you’ve searched for a product on the internet, you’ll probably be served an advertisement for that product or something similar, almost instantly. This can be avoided to a certain extent by clearing the cookies in your browser, going incognito, or using a Tor browser.

But questions have arisen recently as to whether advertisers take it too far by actively recording your conversations without your permission, so as to pick up on what to market to you. As technology becomes more intrinsically connected in our lives, what might be the next furtive marketing tactic or medium in advertising?

Interfaces able to read brain waves have been in development for a while and are getting closer to market launch. While advertising is already heavily reliant on cultivating or playing on consumers’ emotions, what if those emotions could be sensed physically through devices that constantly measure our biometrics. Might this already be happening?

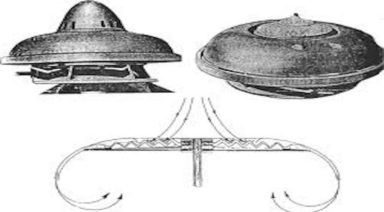

The Navy's UFO Sightings; US Government Recognizes the Phenomenon

Shortly after the Navy Times released “Aliens, ahoy!,” the Washington Post published “Angry Pilot,” and the NY Times asked, “Wow, What Was That?” these heavily promoted and widely consumed articles were immediately parroted by a long list of other popular news sites including CNN, AOL, Yahoo, The History Channel, Live Science, and many others. The upshot? The Navy pilot UFO report and video clearly show an extraterrestrial, “Tic-Tac”shaped ship outmaneuvering the world’s best fighter pilots. Big shocker, right?

Here’s the thing: when a tidal wave of information gateways tote the same content as the most clandestine, conspiracy-minded, UFO messaging boards, it’s vital we take notice. While the government might try to soften the blow of these reports, the truths resulting from the Pentagon UFO program are now officially confirmed.

“Sooner or later, the people in this country are gonna realize the government does not care about them! The government doesn’t care about you, or your children, or your rights, or your welfare or your safety. It simply does not care about you! It’s interested in its own power. That’s the only thing. Keeping it and expanding it wherever possible.”

— George Carlin