A Mexican Scientist Has Cured HPV With Oxygen and Light Frequency

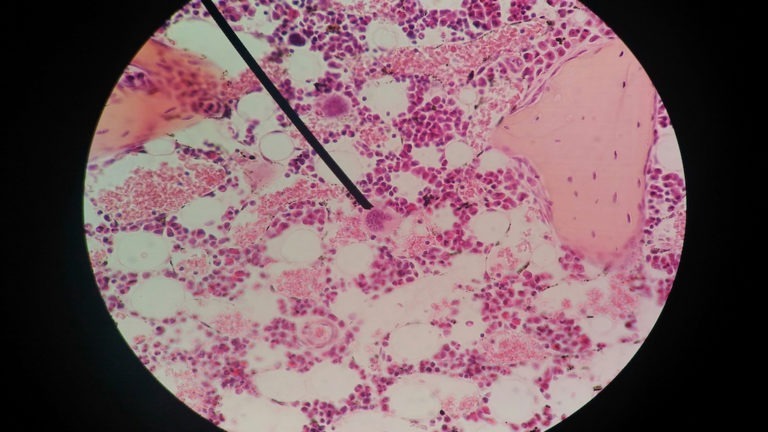

A group of Mexican researchers have found a breakthrough treatment for Human Papillomavirus, or HPV, the sexually transmitted virus responsible for 95 percent of cervical cancer. But unlike most treatments for carcinogenic infections, the team implemented a non-invasive photodynamic therapy that uses oxygen and light frequencies to destroy cancerous tissues.

According to a report in a major Mexican news publication, El Universal, a research team at Mexico’s National Polytechnic Institute led by Eva Ramón Gallegos, was able to completely eliminate HPV in 29 patients in a study conducted in Mexico City.

While this appears to be their first success with treatment in official clinical trials, Ramón said she has been studying its effects for 20 years and used it to successfully treat hundreds of patients. She said she has treated 420 patients in Oaxaca and Veracruz in addition to the recent group of 29.

“During the first stage of the investigation, when it was used to treat women in Oaxaca and Veracruz, the results were encouraging. The treatment was also very positive when applied to women in Mexico City, which opens the possibility of making the treatment more efficient,” she said.

According to her study, Ramón said she eliminated HPV in 100 percent of patients with the virus who had no premalignant lesions – a condition associated with the onset of cancer. For patients with HPV and premalignant lesions she eliminated the virus in 64.3 percent of subjects, and eliminated precancerous lesions in 57.2 percent of those with just lesions but no HPV.

Dr. Ramón and her team. Photo courtesy National Polytechnic Institute

Photodynamic therapy implements a drug called a “photosensitizer,” or a photosensitizing agent, with a light source. When the agent is exposed to certain light frequencies it produces a type of oxygen that destroys cancer cells within close proximity.

The treatment involves the injection of the agent into the bloodstream where it is absorbed by cells throughout the body, remaining in cancer cells longer than in normal cells. Doctors then expose those cancerous cells to light, which produces a type of oxygen that subsequently destroys them.

Photodynamic treatment has been recognized by the NIH’s National Cancer Institute for its efficacy in treating esophageal cancer and non-small cell lung cancer, though this appears to be the first time it has been used for treating HPV and cervical cancer.

Unlike chemotherapy and other invasive treatments for cancer or precancerous conditions, the photodynamic treatment has no negative side effects on nearby healthy cells.

According to the NIH, this type of photodynamic treatment is only effective for treating cancerous tumors just below the skin or on the lining of internal organs, as the light can only penetrate about a third of an inch deep. However, there is another treatment, known as extracorporeal photopheresis, that implements a machine to collect a patient’s blood cells and expose them to photodynamic treatment outside the body, before replacing them in the patient.

Alternative views on cancer treatments have long heralded the idea that natural processes such as light, oxygen, and sound frequency have the ability to fight cancer without exposing our bodies to radiation and other toxins that cause residual damage to healthy cells.

Now that photodynamic treatment is being pioneered to treat viruses and carcinogens, hopefully it will receive further attention and funding for more rigorous and alternative applications.

Wilhelm Reich — Prophet or Madman?

“My present work began in the realm of psychiatry and psychoanalysis. This led to the discovery of bio-energy in the living organism and atmosphere. It follows new, hitherto unknown functional laws of nature.”

~ Wilhelm Reich

Born in Austria at the close of the 19th century, Wilhelm Reich was the son of a Jewish farmer but was deprived of his heritage by parents who raised their children as “Austrians’” a nationalistic, rather than religious, identity. After a complicated childhood and his parents’ deaths, young Reich joined the Austro-Hungarian army during WWI.

After the war, Reich enrolled in law school at the University of Vienna but switched to medical studies early on. At the time, a renaissance of inquiry into human nature was beginning. After attending a talk by Sigmund Freud, then a lecturer in neurology, Reich took a job at the Freud’s Vienna Ambulatorium, an experimental psychoanalytic clinic, soon earning the role of assistant director. Biographers have referred to Reich as Freud’s wunderkind or his prodigy.