What’s Sending These Mystery Signals From 4,000 Lightyears Away?

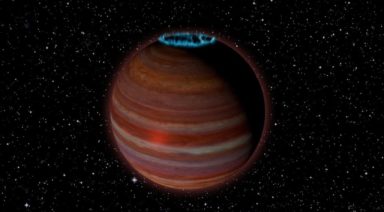

A mysterious repeating radio signal from space has been detected that scientists have not seen before. What or who is sending this signal?

Scientists have detected a radio signal from somewhere out in deep space some 4,000 light-years away.

The signal pulsed every 18 minutes and 18 seconds, for 30 to 60 seconds — every time, 18 minutes and 18 seconds. It did this for three months then it stopped. Scientists assume it is a naturally occurring rotating object that, like a lighthouse shining its beacon, will send what appears to be a repeating signal.

But Natasha Hurley-Walker, whose study into this repeating signal was recently published in the journal Nature told Vice, “[T]here are no models that produce such bright radio emission from two objects in orbit with each other, with such precision, and any that would produce any kind of radio waves would also produce X-ray emission, which we don’t see.”

Some think this might be coming from a highly magnetized star called a magnetar. So what does this all mean? Astronomer and Gaia News contributor Marc D’Antonio weighed in on the subject.

“Maybe this strange signal is some weird kind of magnetar that is rotating, but we’re not used to seeing it rotate every 18 minutes, that means a rather slow rotation. So, this is kind of weird, it’s something that doesn’t match any model that we know, and I think it takes us down a new research path to try to figure out just what it is we’re looking at,” D’Antonio said.

If this signal is not from some type of dead star, what else could it be?

“There is a remote chance, the far remote one, that it’s a techno-signature, maybe. Now, what’s a techno-signature? It’s a signature from something that’s intelligent that’s beaming out something,” D’Antonio said.

“Now, (with) repeating bursts like this we always err on the side of caution and say, ‘[W]ell the universe rotates, everything rotates,’ so, therefore, it could be something rotating and flashing a hot side toward us that has this signal in it like a hotspot. So it could even be something that’s a techno-signature that’s intelligent or it could be a naturally occurring strange kind of exotic star — a magnetar — something along those lines. It’s really odd, you know? Where would it come from? What is the origin of this? How does a star like this form if it’s a star from a supernova? There are really no models that show us how something like this forms. It is really perplexing, and therefore, really exciting.

What about the pulse itself, could there be data within that could be studied?

“The information inside the pulse is something that would be interesting to look at. Was it sending out something specifically? Was it sending a message saying, ‘[T]hey’re coming to you, get off your planet,’ or whatever, I don’t know,” D’Antonio said.

“But I do know that that’s something interesting and I’m sure that no one is really looking inside the pulses to examine the exact nature. Sure they are looking at the signal and what it’s doing, but the signal that’s coming is not like it’s blowing off the airwaves, it’s a very faint signal. But the strangeness isn’t how it’s pulsing, the strangeness is in why it stopped, and the strangeness is in the duration. This is all new, every 18 minutes it would pulse, and it was 18 minutes 18 seconds. That was a very strange pulsation period and as quick as it came, it was gone, and it stopped — and no one knows why it stopped.”

What does this discovery mean for the big picture future of astronomy?

“It’s these one-time things you see that are really exciting because we could be on the cusp of some other kind of discovery. Either way, we are, we are on the cusp of another discovery — either discovering a brand new natural object or discovering possibly that we’re not alone,” D’Antonio said.

Is This a Solution to the Fermi Paradox?

A new theory has been devised on why aliens have never visited Earth, that we know of, as a possible resolution to the Fermi paradox.

Many who are curious about the existence of ETs have heard about the “Fermi paradox,” named after famous astrophysicist Enrico Fermi.

The story goes that in a lunchtime conversation with other astrophysicists who reasoned that, given the vast size and age of the universe it stands to reason, there must be other intelligent life out there, to which Fermi asked, “where is everybody?”

For decades people have tried to answer that question if there are so many possible ET civilizations, where are they? Now, astrobiologists Michael Wong, of the Carnegie Institution for Science, and Stuart Bartlett, of the California Institute of Technology offer their hypothesis, and it’s a bit dark.

Using studies of the growth of cities on Earth, they argue that civilizations grow infinitely but in a finite time. This infinite growth of population and overuse of energy will eventually lead to the death of the civilization or possibly saving themselves.

“We propose a new resolution to the Fermi paradox: civilizations either collapse from burnout or redirect themselves to prioritizing homeostasis, a state where cosmic expansion is no longer a goal, making them difficult to detect remotely.”