Consciousness Might Be Explained By Multiple Personality Disorder

The idea that our sentience may be the product of a conscious universe experiencing itself is not a new one – in fact, it’s the central philosophy behind more than one religion, i.e. Hinduism, Buddhism. But now, a paper published by philosopher Bernardo Kastrup, has laid out a convincing argument to reconcile this idealist theory with dissociative identity disorder (DID), otherwise known as multiple personality disorder.

Those suffering from DID exhibit at least two disparate personalities experiencing reality through distinctly separate lenses, despite inhabiting the same physical body. These personas, known as “alters,” can sometimes be completely unaware of each other’s being, compartmentalizing their lives and essentially leading parallel existences.

Scientists discovered that DID sufferers’ various alters can affect attributes of the body to the point that brain functions will literally change when a new personality takes over. For instance, EEG tests showed that the region of the brain associated with vision actually shut down while a blind alter took over a patient’s body. When a sighted alter took over, that region of the brain resumed normal function.

It’s undoubtedly difficult to lead a normal life if you suffer from DID, but if it’s possible for this level of dissociation, in which multiple personalities with their own sense of individual self can occupy a single psyche, then what’s to say that an analogous mechanism isn’t at work in the relationship between our individual consciousness and a greater universal consciousness?

Kastrup likes to call this universal consciousness “mind at large,” and he describes our relationship with it like the essence of a tree. Our individual psyches branch off in their own directions, but at their roots beneath the soil, they grow out of a greater individual organism. And the reason we’re unable to see that connection is due to that layer of soil, or what Kastrup refers to as the obfuscation of our collective consciousness.

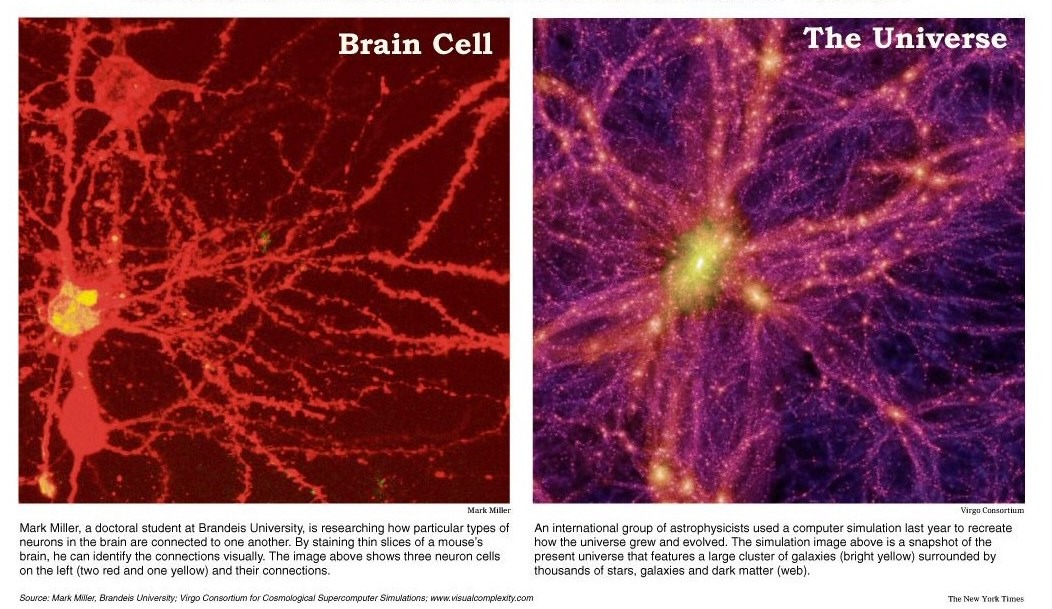

Maybe a better example of this can be seen through the individual neuron in the brain; a microscopic cell that receives, processes, and transmits information through electrical and chemical signals. There are billions of individual neurons throughout the brain, connected through dendrites and axon fibers, which pick up small bits of data to transfer and inform the greater organ as a whole.

Our individual consciousness is much like an individual neuron in the brain, receiving, processing, and transmitting data between other neurons within synapses and neural circuits, informing the greater whole we call society and humanity. This comparison is even more intriguing when you compare images of a simulated map of the known universe with the brain cells of a living being; the similarities are uncanny.

Kastrup is a staunch opponent of the materialist view that our mind is a product of the brain. This view says that the physical world, or matter, is the fundamental substance of nature, and that it dictates reality. It says our minds, and subsequently our consciousness, can be reduced to the product of predictable, physical interactions in the brain, explained through metrics such as mass, momentum, charge, and spin.

But materialism has an irresoluble issue, known as the hard problem of consciousness; that these metrics used to define matter can’t be applied to our subjective experience of reality. We have no universal measurement to describe the way something makes us feel. Try explaining the color red or the happiest you’ve ever felt – qualia prevent our consciousness from being defined by these standards.

And according to Kastrup, any attempt to solve the hard problem of consciousness by viewing consciousness as the product of our reality is futile. Conversely, viewing reality as the product of our consciousness makes the hard problem of consciousness a moot point. You can’t prove that this reality exists without consciousness, and if we continue to try to argue this point we find ourselves trapped in circular reasoning.

There’s no consciousness in our body/brain system, our body/brain system is in consciousness. Our brain is a second-person perspective of a first-person experience. These are Kastrup’s intrinsic tenets.

When we look back at the cosmos, or our reality, we’re observing the universe’s mental processes outside of our own individual alter. Our lives are a dissociative process of the universe’s consciousness and everything we see is simply another dissociative process of the mind at large.

Has Kastrup’s monistic idealism solved the hard problem of consciousness or simply sidestepped it?

Watch the documentary Conscious States of Dying in which Stanislav Grof discusses various cultures’ perspectives on our state of consciousness after death:

New Theory Says Consciousness is Electromagnetic

For centuries, humans have tried to determine ‘what is consciousness?‘ How are we able to think and have free will? A new scientific theory says consciousness may be electromagnetic.

Philosophers and scientists have debated the nature of consciousness for years. Consciousness put simply, can be defined as capable of, or marked by, thought, will, design, or perception. But where does this ability come from? Inside the brain or some external force?

Johnjoe McFadden professor of molecular genetics at the University of Surrey has a new theory he calls the Consciousness Electromagnetic Information Field Theory, or CEMI Field Theory.