Uncovering the Ancient City of Eridu

Depending on how much of an ancient history buff you are, there’s a good chance you’ve heard of Eridu.

This ancient city, said to be one of the oldest in the world, is located in what is today Iraq and better known as Abu Shahrein.

Today, few remnants remain of Eridu. You may wonder how such a seemingly random place was once anything of great importance. By examining Sumerian mythology, architecture, Genesis, and texts, we find a rich and intriguing picture of what it once was.

While many ancient Mesopotamian cities have unique aspects, Eridu’s purported definition of “guidance place” makes it particularly noteworthy.

However, given the large structures found therein, as well as its perceived importance among other ancient cities of the time, the definition of “mighty place” might be the most appropriate for the ancient city of Eridu.

Ancient Sumerian City

According to Sumerian mythology, Eridu is said to have been one of the oldest cities in Mesopotamia. It was believed this ancient location was created by the god Enki, also known as Ea, or the god of wisdom.

In Sumerian mythology, Eridu is allegedly one of the five cities built in this region before the Deluge, or Great Flood, occurred and is still argued by many to be one of the oldest cities in the world.

Eridu is also listed as the city of the first kings in the Sumerian King List.

Temples of Eridu

Excavations of the Eridu site in the last couple of centuries offered more insight into additional layers of the city, perhaps most prominently its architectural structures.

For example, during excavations of Eridu on Mound 1, 18 successive levels of mud-brick temple architecture were uncovered. Eridu’s claim to fame when it comes to architecture is most likely its temples, also known as ziggurats.

These grand structures had the form of a terrace-step pyramid, with successively receding levels. Each ziggurat was part of a larger temple complex, which included other buildings. Inside, they often consisted of a small room and offering table.

This temple of Enki in Eridu also contained a holy tree in a holy grove, which was the central point for the king to perform various rites, as he was known as a “master gardener.”

Because Eridu’s ziggurat ruins are older and larger than any others, some believe these ziggurats are those mentioned in the Bible when referencing the Tower of Babel. The Tower of Babel was said to have been created not for the worship and praise of a God, but to glorify the builders of the temple itself.

Eridu Genesis

Beyond the architecture of Eridu, much of what is known about its beginnings come from the Eridu Genesis, a Sumerian text written on a cuneiform tablet. Unfortunately, two-thirds of the content in these tablets has been lost. However, much of these parts can be reconstructed by using other texts.

The Eridu Genesis texts cover many topics, most notably the creation of man, first cities, building of the ark, the Great Flood, etc. Many such items directly correspond with similar accounts referenced in other texts of the time, such as the Bible.

For example, within the Eridu Genesis, it states the gods created mankind to farm, herd, and worship them. According to its account, Ziusudra from Eridu was instructed by Enki to build a boat to survive the Deluge or Great Flood.

This account largely mirrors that of the Bible, which credits Noah with the creation of the ark for similar purposes.

Incantation of Eridu

Other texts linked to Eridu connect it more closely to Sumerian magic and myths.

These writings, in particular, the Incantation of Eridu, were believed to compel the gods in the name of Marduk, a significant deity of Mesopotamian religion, which began a larger system of magical hierarchies. This incantation has been credited with the source of power for Mardukite magic.

Some of what is known about such magic has been gained from these ‘spiritual’ or ‘magical’ cuneiform texts. According to studies of Mesopotamian magic, priests learned prayers such as the Incantation of Eridu to compel the gods in the name of Marduk.

Through such structures used by those practicing Mesopotamian magic, it is said magical hierarchies were created.

Certain such powers were said to have been sealed in Eridu, such as petitions to assume god-form, wherein the individual would continue a ceremony or proceeding, acting as a divine representation of the God ‘invoked.’ This practice has similarities with other religious practices, such as in a Catholic priest taking on a Christ form in imitating and reenacting the Last Supper.

Eridu: City of Mythology and Magic

Many ancient Mesopotamian cities have intriguing aspects about them, and Eridu is certainly no exception. Thanks to its ties to Sumerian mythology and magic, Eridu is a fascinating city to explore through further research. Although the Eridu of today is largely sand dunes, remnants of what the complex city might have been in the past suggest it was indeed, a mighty place.

Its old age alone sets it apart from similar Mesopotamian cities. In addition, the Temple of Eridu, Eridu Genesis, and Incantation of Eridu are all remnants of this city’s history that seems to invite more research and interest, as they connect the Sumerian faith with other religions still practiced today.

Want more like this article?

Don’t miss Ancient Civilizations on Gaia to journey through humanity’s suppressed origins and examine the secret code left behind by our ancestors.

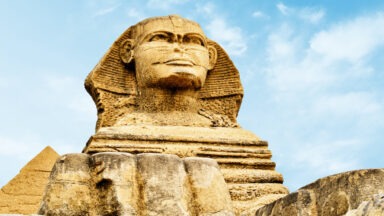

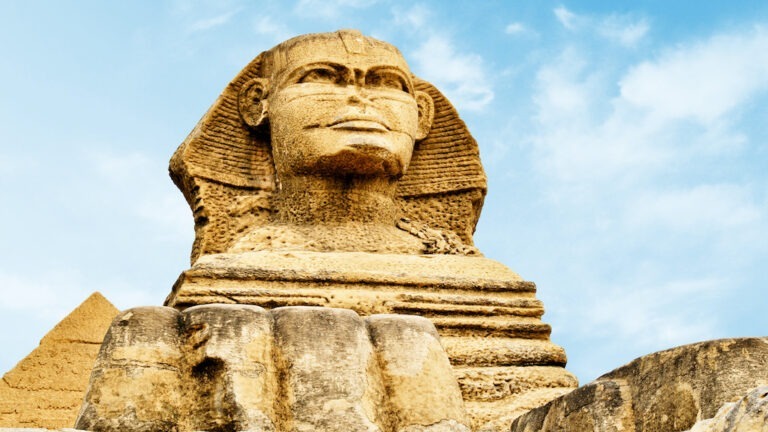

Decoding the Actual Age of the Great Sphinx

The Great Sphinx of Giza is widely believed to be around 4,500 years old, constructed during the reign of Pharaoh Khafre around 2500 BCE. But some researchers argue it could be far older, even 10,000 to 12,000 years old, based on geological signs of water erosion and other conflicting evidence. This ongoing debate challenges the accepted history of Egypt and the origins of human civilization.

Posing as a sentinel on the Giza plateau is the weathered and colossal figure that stands 66 feet above the desert sand, the Great Sphinx, a limestone sculpture with the head of a lion and the body of a human. While we now know much about the history and mythology of the ancient Egyptians, the mystery of the Sphinx has yet to be truly unraveled.

An ongoing battle between mainstream Egyptologists and a more recent wave of independent thinkers debates the age of the Sphinx by thousands of years. The latter insists the imposing limestone statue is much older than mainstream archaeologists, and Egyptologists claim it to be.

Mainstream archaeologists determined the Sphinx to have been built between 2558 and 2532 BCE. But in 1992, John Anthony West rocked the scientific community with his claim that the Sphinx was actually carved 10,000 years earlier before Egypt was a desert. West and others argued that academia had overlooked an important detail—the body of the sculpture bore distinct markings of water erosion.

After his assessment of the Sphinx’s age, West found fellow scientists who shared his observation about uncovering an entirely different history than was commonly accepted. West’s search led him to Robert Schoch, a geology professor at Boston University, willing to pursue an open-minded, out-of-the-box investigation into the origins not only of the Sphinx but the entire region, as well as its implications for the origin of the human species.

In Gaia’s original series, Ancient Civilizations, Schoch explains his first encounter with the figure in 1990, at which time he immediately noticed there was a disconnect between the statue’s academically accepted date of origin and the truth staring him in the face. Upon careful inspection, Schoch realized the Sphinx survived intensely wet weather conditions that stand in stark contrast to the now hyper-arid conditions of the Sahara Desert.

Schoch concluded that academia had determined the Sphinx’s age by overlooking signs of erosion due to heavy rainfall. The deluge that eroded the Sphinx was uncommon to the Egyptian plateau 5,000 years ago, but very common 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. For Schoch, this was an exciting find, but for mainstream science, it was met with derision and denial.