Tobacco Ties: Honoring Earth the Lakota Way

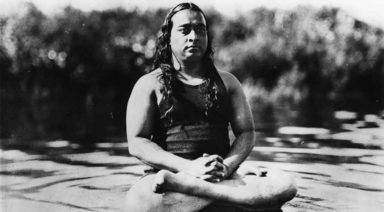

Zintkala Waste (pronounced: Wash-tay) was born on a full moon in a tent on the South Dakota Rosebud Reservation in the Upper Cut Meat community. “I grew up spending all my time learning traditional ways with the elders. I was taught about everything Lakota,” he says. With his calm, warm presence, he embodies an archetypal grandfather.

Speaking quietly, he adds that he is a member of the Burnt Thigh Clan of the Rosebud Lakota Tribe, and that one day after he was born, he was given his Indian name, “Zintkala Waste,” meaning “Good Bird” in Lakota.

As a spiritual leader and minister of the Native American Church, he says that one of his duties is to hold sweat lodge ceremonies. “I also teach what I’ve learned over my lifetime. I help people with alcohol and drug problems. Since I will be 76 on May 30, 2018, I am one of the elders of the tribe,” he says.

Giving Thanks to the Earth

In the Lakota tradition, honoring the earth, known as “Maka Iyan,” is a way of life. Generations of Lakota people have made tobacco ties; a traditional offering to the earth, the spirits, and the creator, called “Wakan Tanka.” Zintkala summarizes the Lakota people’s indivisible relationship with Maka Iyan in the simplest possible terms, saying,“the earth is first.”

All his life, Zintkala has ceremonially offered the tobacco ties he learned to make as a child. But the traditional plant material used in the midwest and western parts of North America is not the smoking tobacco grown in the southeast — it is what the Lakota call cansasa (chun-sha-sha); the native red willow that grows wild along creeks and rivers. Zintkala says, “It is picked and dried, and has been used as tobacco for generations before white men arrived. We still use it, and there’s still a lot growing locally.”

Zintkala shared instructions about making and using the ties for those who would like to celebrate Earth Day the Lakota way. The act of making ties requires focus and attention, recalling many well-known mindfulness meditation practices.

Q. How do you make tobacco ties?

Cut a square from cloth and put a pinch of tobacco in the center and tie it off (see video). Connect the ties with string to make a long string of them. Or arrange them in groups, according to the prayers and intention. Make ties for each of the four directions; south is red, west is black. north is white, and east is yellow.

Q. When you make the ties, do you hold an intention?

Yes. Definitely. One way is offering the tie to the Great Spirit as you make it — but offer it to whatever name you use for the creator. If you want something done, ask the Great Spirit to help. If you want help, consider the problem and ask the Great Spirit how many ties you should make for each direction. You’ll get an answer if you’re patient.

You can also use ties for protection by making them with that intention then hanging them in your house. You need patience and real focus when you sit and makes ties, because it’s tricky, and it takes a long time. When you offer the ties, you have got to have sincerity and good intention.

Q. How are the ties offered?

Here’s an example. I’m rebuilding my sweat lodge now, and I’ll make 25 tobacco ties for each direction and tie them to the inside walls of the new lodge. The ties will be made with prayers for healing, peace, honoring ourselves, for our loved ones, honoring elders and the tunkasilas (grandmothers and grandfathers), and for the home of the farmer who owns the land where we build the sweat lodge.

They can be tied on a tree branch out in an isolated place that has special meaning or needs prayers. Ties can be made with a pledge attached to them so that you can come back next year and be connected to the place solidly.

They can be put in the home in places where prayers are needed; then taken down later, often four or five days. If we have a special request to Wankan Tanka (Great Spirit), they can be tied to the sides of the sweat. When we do vision quests, we make enough tobacco ties to encircle the ground we sit on.

When we are finished with the tobacco ties, they might be burned in a sweat lodge fire. You can also get rid of the ties by burning them with sage, which takes the prayers in the smoke to tunkasilas (grandparents).

There are a lot of ways to use tobacco ties, but it has to come from the heart.

Zintkala Waste in ceremonial garb.

What is Voodoo? A Tradition of Magic and Interconnected Realms

When the word “voodoo” arises, it’s usually accompanied with misconceptions, fear, and a lack of understanding. Often thought of as a violent cult, the truth couldn’t be farther from the popular cultural associations, such as voodoo dolls, witchdoctors, and violent-tinged sorcery. Voodoo, more appropriately known as vodou, is an ancient and diversely practiced religious tradition tied to Africa, the Caribbean, and the Catholic church.

But what exactly is Vodou?

Voodoo: A Rich Tradition Born From Trauma

The word Voodoo/Vodou/Vodun translates to mean “the spirit of God.” Vodou is a monotheistic religion; followers, or vodouisants, believe in one divine figurehead called Bondye, or “the good god.” Additionally, Vodou has a lesser god hierarchy, Iwa, as well as Ioa who are more engaged with the day-to-day life than Bondye, who is considered to be more remote. The Ioa/Iwa are split into three families: Rada, Petro, and Ghede. Humans and Lwa have a reciprocal relationship in which believers provide sustenance and objects in exchange for the Lwa’s protection.

Vodou combines traditions from Africa, the Caribbean, Native Americans, and Catholicism. There is evidence that as far back as 1492, many in the Taino culture were executed for their practice of Vodou during Christopher Columbus’ conquering of Hispaniola. But as the slave trade grew, so did Vodou; the newly arrived African slaves and the surviving Taino found much in common in their shared rituals and approaches to healing.

Vodou does not have a central scripture, it is community-centric and supports individualism. New Orleans is North America’s vodou epicenter, where it arrived through the slave trade from West Africa during the 18th century. Catholicism was the primary religion in the city, and what is now known as “New Orleans Vodou,” is in actuality a hybrid between the two traditions. New Orleans Vodou has become so ingrained in the city’s culture that one need only search online to see the multitude of shops, tourist attractions, and other popular destinations that keep the tradition alive.