Study Shows Consciousness May Be Product of Quantum Effect

A controversial theory on consciousness has just been tested: Could consciousness be explained by quantum effects in the brain?

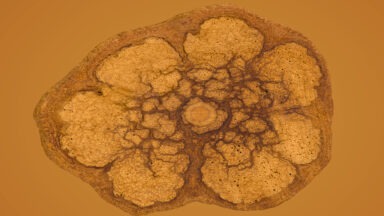

A 30-year-old theory on consciousness called, “Orchestrated Objective Reduction,” posits that consciousness could live in tiny microtubules in the brain, or as New Scientist explains, “Brain microtubules are the place where gravitational instabilities in the structure of space-time break the delicate quantum superposition between particles, and this gives rise to consciousness.”

The theory was first introduced in the 1990s by physicist Roger Penrose and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff, but was believed to be untestable and was therefore regarded as a fringe theory at best.

But now, New Scientist reports the theory has just passed a key test, writing, “Experiments show that anesthetic drugs reduce how long tiny structures found in brain cells can sustain suspected quantum excitations. As an anesthetic switches consciousness on and off, the results may implicate these structures, called microtubules, as a nexus of our conscious experience.”

In one experiment Jack Tuszynski at the University of Alberta shone blue light on microtubules, the hollow skeletal structure inside plant and animal cells, to see how they react. The light was caught in the microtubules and then re-emitted in a process called “delayed luminescence,” which they say is comparable to how the human brain processes information. and, they argue, could explain the fundamental workings of the brain and consciousness.

The second part of the experiment was to repeat it but in the presence of an anesthetic. The anesthetic suppressed the delayed luminescence in the microtubules, meaning the light was re-emitted faster after the anesthetic shut down the microtubule. So what does it all mean? Tuszynski believes that turning consciousness on and off via microtubules could be the beginning of our consciousness.

However, Fred Alan Wolf, physicist, lecturer, and author of “Taking the Quantum Leap” is skeptical about the role of microtubules.

“Somehow we don’t feel microtubules are the final answer, if at all the answer,” Wolf said. “Maybe it’s the mission of the light that has something to do with consciousness, and maybe we’re knocking out the microtubules by putting anesthesia onto them. So, that was the hypothesis, the guess, the tying together of the timing of the emission of re-emitted light to anesthesia to consciousness. So, eh, how would you prove it? It’s an interesting concept. Who knows whether it’s right or not — I doubt whether it’s right, it’s too simple.”

As someone who has studied consciousness for decades, what do you think is the answer?

“What consciousness is, is very difficult to say,” Wolf said. “A better line of research would be to try to determine what consciousness does. Can we actually point to things that are happening that we can attribute to consciousness itself?”

Much more testing is needed on the microtubule hypothesis, even Tuszynski himself told New Scientist, “We’re not at the level of interpreting this physiologically, saying ‘Yeah, this is where consciousness begins’, but it may.”

Psychic Abilities May Stem From a Field of Consciousness

Ever have the feeling that you know you’re being watched? Or the feeling of thinking about someone just before they call? Some believe these feelings are merely coincidental or just happenstance, but the fact that they are common and something everyone can relate to, leaves open the possibility that there could be a metaphysical mechanism at play. Now, researcher Rupert Sheldrake says he believes these occurrences are due to a psychic phenomenon that is evidence of a collective consciousness and he’s found this theory to show statistical significance.

Sheldrake is most famous for his theory of morphic resonance, a concept that revolves around psychic capability, which he believes is innate in humans and animals. Morphic resonance states that processes and behavior in nature, particularly learned behavior, can be inherited and transmitted psychically. This theory has made him somewhat of a pariah in the scientific community, which labelled him a heretic for entertaining such a seemingly nebulous concept. Nevertheless, he embraces the criticism and continues to pursue his research.