Bicycle Day 2022 – 79 Years Since Albert Hofmann’s LSD Discovery

Eight years before Albert Hofmann first synthesized LSD in 1938, Harry J. Anslinger was appointed the founding commissioner of the U.S. Treasury’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics. While both men were of Swiss descent and their life’s work centered around public drug use, their paths couldn’t have been more divergent. And now for this year’s Bicycle Day, as the tides of drug policy are shifting quicker than ever, their stories are increasingly relevant.

While most consider the United States’ war on drugs to have started with the Nixon or Reagan administrations, author Johann Hari in his book Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs, urges our reconsideration of the country’s infamously failed attempt at drug prohibition to an earlier date.

Hari argues that based on racism, classism, and other prejudices, Anslinger was largely responsible for creating a zeitgeist of public misconception about nearly every drug, without regard to therapeutic applications or larger societal implications.

And though Anslinger’s tenure ended just before the criminalization of LSD, it was the foundation he set in place that widely villainized the chemical for decades.

But with the recent relaxation around psychedelic substances and the recognition of their potential as powerful healing modalities, Hofmann’s radical discovery may finally be realized for what he envisioned it could be.

The History of LSD

Albert Hofmann laid out his serendipitous discovery of LSD in the autobiographical account LSD: My Problem Child, prefacing his breakthrough with an ineffably spiritual and prophetic walk in the woods as a young boy:

“One enchantment of that kind, which I experienced in childhood, has remained remarkably vivid in my memory ever since…. As I strolled through the freshly greened woods filled with bird song and lit up by the morning sun, all at once everything appeared in an uncommonly clear light. Was this something I had simply failed to notice before? Was I suddenly discovering the spring forest as it actually looked? It shone with the most beautiful radiance, speaking to the heart, as though it wanted to encompass me in its majesty. I was filled with an indescribable sensation of joy, oneness, and blissful security.”

“I have no idea how long I stood there spellbound. But I recall the anxious concern I felt as the radiance slowly dissolved and I hiked on: how could a vision that was so real and convincing, so directly and deeply felt—how could it end so soon? It seemed strange that I, as a child, had seen something so marvelous, something that adults obviously did not perceive – for I had never heard them mention it,” Hofmann wrote.

It’s hard to read Hofmann’s account and not feel an eerie, mystical sense of foreshadowing, as if the universe had given him an early glimpse into the profound sensation of his most famous discovery.

Many are familiar with the rumored story of Hofmann’s breakthrough, which claims he accidentally dosed himself with LSD before later taking an intentional dose as well as his famous bicycle ride home as the first person (in modernity) to experience the drug’s hallucinatory effect.

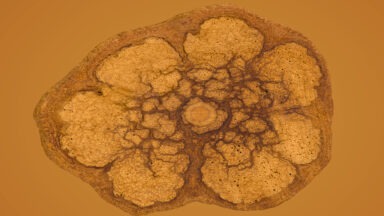

Hofmann named his compound LSD-25 because it was his 25th iteration isolating the drug from ergot fungus, one of three organic plant substances he was tasked with studying. Ergot fungus was known in times of antiquity as being poisonous in large doses, but certain synthetic variants were found to be effective treatments in obstetrics.

So, when LSD-25 only produced 70 percent of the expected hemostatic (blood coagulating) effects of similar ergot derivatives, it was shelved for its inferiority. Little did Hofmann, or his colleagues, know the potent psychedelic effects it held — at least not yet.

But something in Hofmann’s subconscious did know. Despite the fact that when a compound was shelved it was typically never tested again, Hofmann felt an uncanny desire to give it another look.

“The solution of the ergotoxine problem had led to fruitful results, described here only briefly, and had opened up further avenues of research. And yet I could not forget the relatively uninteresting LSD-25. A peculiar presentiment—the feeling that this substance could possess properties other than those established in the first investigations—induced me, five years after the first synthesis, to produce LSD-25 once again so that a sample could be given to the pharmacological department for further tests,”

— Albert Hofmann

Hofmann convinced his superiors to let him test the compound one more time, despite what he described as a frugality in these types of situations at Sandoz, due to a lack of resources.

But this time, after he once again synthesized a tartrate solution of LSD-25, Hofmann suddenly reported “dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of paralysis, and a desire to laugh.” He realized that during the compound’s crystallization, he had accidentally absorbed a trace amount through his skin.

Hofmann rode his bicycle home, accompanied by his lab assistant, seeing the world through wavering, kaleidoscopic vision. But after just a few hours he found his trip starting to wear off, due to the relatively small dose he unknowingly took. So, he decided the only logical next step was to “self-experiment” again a few weeks later. This time with a larger dose.

Hofmann convinced his colleagues of the magnitude of his discovery and soon they were “self-experimenting.” And the rest, as they say, is history…

Sandoz patented and distributed LSD for psychotherapy under the pharmaceutical name Delsyid, even recommending psychiatrists take the substance themselves to better understand their patients’ headspace when it was administered to them.

According to documents published by Sandoz, “in minute doses” LSD had the ability to “produce changes in emotional behavior, hallucinations, depersonalization, and reliving of repressed memories.”

Hofmann and his colleagues believed it was a useful treatment for confronting and working through psychological trauma. But soon enough LSD’s potent psychoactive effects were noticed and subsequently weaponized by the CIA for the notorious Project MKUltra, which looked to employ the substance as a tool for mind control.

Conversely, LSD also became a tool used by the hippy generation of the 60s to spread love and peace, extolled by notable counter-culture leaders, including Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, and Ken Kesey.

But the US government quickly perceived the use of LSD and other psychedelics as a threat which debased social and political hierarchies that kept people divided by race, gender, and class in order to maintain power.

Instead, psychedelics gave people a sense of oneness and unity that was palpable in an era of war and division.

Hofmann even noticed this effect when he administered LSD to monkeys in clinical studies:

“A caged community of chimpanzees reacts very sensitively if a member of the tribe has received LSD. Even though no changes appear in this single animal, the whole cage gets in an uproar because the LSD chimpanzee no longer observes the laws of its finely coordinated hierarchic tribal order,” he wrote.

Needless to say, LSD and almost every other known psychedelic was criminalized in a sweeping piece of legislation known as the 1970’s Controlled Substances Act, despite 1000s of scientific publications throughout the ‘60s touting the substance’s psychotherapeutic benefits.

But now after decades of oppressive drug laws that have exacerbated the racism, classism and oppression first initiated by Anslinger in 1930, it seems we may be on the precipice of truly progressive drug reform surrounding psychedelics. Thanks to groups like MAPS, the Beckley Foundation, and clinical studies by researchers at esteemed institutions, significant headway is being made to dissolve the antiquated stigmas and throughly prove their therapeutic elements.

And now, with states voting to decriminalize or legalize psychedelics for medicinal use, we may be coming full circle in recognizing these substances' true potential.

For more on the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics check out the documentary Neurons to Nirvana:

Study Shows Microdosing Psilocybin Boosts Mood, Mental Health

A new study provides the most compelling evidence to date on the impressive mental health benefits of microdosing psilocybin.

While there has been an ever-increasing number of studies showing the efficacy of treatment of mental health disorders with psychedelics, there has been relatively little research on the practice of microdosing.

Microdosing, or repeatedly taking small, barely perceptible amounts of psychedelics, has been exponentially increasing in popularity, with a wide range of people reporting a multitude of improvements to their psychological wellbeing.

The latest scientific study to look at the effects of microdosing was conducted by researchers at the University of British Columbia, as well as other leaders in the fields of psychology and mycology. The study followed 953 people who used small, repeated doses of psilocybin for about 30 days, as well as a control group who did not microdose.

While the exact dosages of psylocibin that participants self-administered varied somewhat, they were all low enough to not impact daily functioning.

Over a one-month period, participants took these psylocibin microdoses three to five times per week and were asked to complete a number of assessments through a smartphone app that tracked their mental health symptoms, mood, and measures of cognition. The findings definitively showed that the microdosing participants demonstrated greater improvements in mood and mental health than those in the non-microdosing control group.